- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 18

Taína Read online

Page 18

“I’m fine,” she said nicely through the closed door. “I’m fine.”

My father looked at me, asking what happened. I repeated that she was fine. He asked again what had happened. I said nothing. He squeezed my shoulder, letting me know he did not believe me, but just then he heard one of his pots overflowing and he ran back to the kitchen.

The last dog I was to take back was still running around. I fed him, but he didn’t want to eat because my father must have fed him already. I went to my room and looked through some of my books. I could not read and put the books aside. I thought about Peta Ponce, about the two doves becoming angels and fighting to be Usmaíl’s father. I thought, Why should I believe only in one thing? The inner heavens were so large that there was enough room to believe in everything. Peta Ponce folded time in order to change definitions and meanings so scarred women could find peace. I was at peace, too, because the revolution had occurred. And the only one who needed this definition was me.

I heard a knock. I thought it was my father because Mom just entered. But it was her. She was not crying or anything and she was wearing the earrings I had bought her. Her face was gentle and polite, expressions she showed only in public. She asked for permission to sit on my bed. I laughed a little and told her, “Yeah, you bought it.”

“I never meant when I said pa’ Lincoln,” she said nicely. “I would never leave you at that hospital.” This made me happy because I had always believed that she might. “But if I did leave you, I’d visit you every day.” She knew herself well, because when Mom is angry she is capable of anything. God help you if you ever doubt a Puerto Rican woman.

“Ma,” I said, but she didn’t let me say anything after that. She asked me if I missed not having any brothers and sisters. I didn’t answer because she wanted to tell me things she had never told and would never tell me again.

“You like that girl. Una madre sabe.”

“Yeah,” I said. “She’s something like you, I think?”

“Kids are like their parents, and if Taína is like her mother, she’s…”

“Talented? Taína is talented. Like her mother, she can sing,” I said.

“Fine. But that’s not what I meant.” Mom’s nose began to run again. “I know Inelda. She’s crazy.”

“We are all crazy, Ma. The whole world is crazy.”

And Mom pressed her lips tight and nodded in agreement. “Okay, pero hay locos y hay locos,” she said, excusing herself as not being as crazy as Taína’s mother or the rest of the world. “I was not crazy. I just wanted to help my friend. You know, to make it up to her for not being there for her when she wanted to sing. You know, for leaving her—for that…stupid musician.” My mother looked at me. I was sad and she knew I was sad, and she was sad, too.

“But it’s more than that.” Mom said that really fast, as if she needed to get it all out of herself before she changed her mind. “I didn’t want you going down there because Inelda did it. Ella lo hizo. Right after she had Taína she did it. And I went with her. I didn’t talk her out of it. I went with her. I knew where to go because tú sabe’.” Mom’s eyes were on the floor. “We were both raised—” She swallowed and picked up in midsentence: “Puerto Rico was full of women, so many that la operación begins to feel like it’s nothing.” At that moment that word hung in the room like a mist that refuses to die when the humidity is as thick as a wall. “It did not affect me the way it affected Inelda. When Inelda began talking to herself, I took her to see Peta Ponce. She had helped me after you were born, after I did it.” She stood still, sitting on my bed. Mom was breathing deeply, but she was not yet crying, though I knew it was coming. “I didn’t tell the elders,” she said, and I knew why: she would have been kicked out of the church. Looking at the floor where I had thrown my dirty socks, she didn’t say anything for a few endless seconds and just sat there. “Your father knows, of course.” She finally found my eyes. “I was worried that with more children and him not holding jobs, you know, I was scared. After you I was scared.” And I knew that after that she had shut down. There was no need or use for me to press her on anything.

“Ma,” I said, “it’s okay.” And I embraced my mother. Her eyes were wet and she could not speak, but that was okay. There was nothing more she needed to tell me or anyone else.

“Ma,” I whispered, “Peta Ponce is downstairs.”

Verse 4

TAÍNA WAS IN my house. My father was so nice to her. Every second he kept asking her if she was comfortable. If she needed water. If she needed something to eat. And it made me happy to see my father fall for Taína, too, in his own way. My father had cooked all these great dishes from both Puerto Rico and Ecuador. They sat at our dinner table waiting for Peta Ponce, Doña Flores, and my mother to come out of the bathroom, because that was where Peta Ponce said the spirits wanted the women to talk things over.

I was sitting next to Taína in the living room. The last dog, which I could not find the reward flyer for to save my life, was barking happily.

The women in the bathroom were loudly whispering.

We could hear them murmuring at the past.

My father, Taína, and I tried to pay no mind to what was happening in the bathroom. In his broken English, Pops asked Taína if she felt okay. If she wanted to eat.

“Sí, muchas gracias,” she said, very un-Taína-like.

My father went to make Taína a plate, but only for her; the rest of us would have to wait till the misa was over. And Taína held my hand.

“I liked your stupid story. Stupid but kinda pretty,” Taína said.

“What story?” my father asked, and then thought again. “Oh, the revolution in the body, yes, yes. Claro.” He coughed, because he never believed. He was free to understand it any way he wanted.

“I always knew you were looking at me.” Her face got really close to mine and she whispered in my ear, “But I let you.” And my world became new.

Doña Flores and my mother were both yelling about their youth, things and events we could barely make out. There was pounding on the walls and yells and screams in English, Spanish, and Spanglish as I heard, “Yo te trasteo.” My mom yelled that she trusted Peta Ponce and her friend.

The loud voices coming from the closed bathroom door were too much for my father. He breathed out an uncomfortable sigh because this had all been my mother’s idea.

“Pa,” I said, “it’s not as crazy as it sounds.”

“You think so?” he said in Spanish, smirking.

“Okay, well, this is how Mom deals with her mental stuff, this is her shrink.”

“Where are these spirits?” My father’s mocking tone was becoming more and more impatient. He had not seen any ghosts, only a black, dwarfed woman with a hunchback, who had locked his wife and her friend in the bathroom. And worse, the dishes he had cooked were getting cold.

“They are all around us.” Taína’s voice was laced with sarcasm. “They are making faces at you right this minute and you don’t even know it.” She laughed, but my father didn’t think it was funny.

“Bah.” My father had seen enough. He went to where the little dog was and put the leash on. “I’ll be back when this is over.”

I was now alone with Taína. Her stomach was almost ready to set Usmaíl free. I wanted to kiss her. She knew I wanted to kiss her, but it was nice just to be sitting in my living room with her.

“You knew I was looking at you?”

“Of course, shithead, and you give the worst foot rubs. My feet were hurting more afterward than before your dumb-ass massage. Fuck, you are the worst,” she said.

The yelling stopped. We heard a faucet turn on and the extension of a shower curtain. We heard Peta Ponce say words we could not make out.

When it was all over, three women came out of that bathroom, wet and new. All walked into Mom’s room to change and eat.

In Spanish, as that was all she spoke, Peta Ponce told my mother and Doña Flores that their wounds were deep and that seeking a mental health expert would be a good thing. Peta Ponce said not to be misled by how generous the spirits were today, that things could fall apart at any given time. And so to continue seeking help. My mother looked my way because it was now her turn to see a shrink.

“I’ll go with you, Ma,” I said, and she just made a face.

And then Peta Ponce began to laugh. A low, continual laugh. None of us knew what to make of it. So we laughed, too. We were all laughing, with a bunch of untouched food in front of us, waiting for my father so we could all eat. Peta Ponce laughed. And the phone rang. We were one of the last families in Spanish Harlem to actually have a landline. Peta Ponce pointed at the phone.

My mother picked the phone up.

My father had been arrested.

Verse 5

MY FATHER HAD wandered down to the Upper East Side. Someone had recognized the dog. I had to confess so he could be set free. I was taken into a room for questioning. Cops put handcuffs on me even though there was nowhere to go. I was surrounded by like twenty cops standing around a kid. They were congratulating themselves. They took pictures with me. This was the guy we were after. This was the guy stealing all those dogs. We got him. And none of those cops went off to fight real crime. They just stuck around as if I were a powerful superhero with a cape and needed heavy security. The people whose dogs I had been borrowing were mostly powerful Upper East Side women. They were powerful because they were married to powerful Upper East Side men. These women didn’t really work. They just attended these New York society parties. They also made sure all of New York City knew about my crime. Lots of camera crews, The New York Times had sent reporters to cover the story. The New York Post brought my father into it with the headline SON OF BITCH. Reporters and photographers were everywhere.

Then a white, heavy detective walked in. He had a potbelly and smelled of sweat. Then he placed a knife on the table.

“Is this your knife?” Though he must have known it was because he must have searched my room.

“Yes,” I said, “that is my knife.”

“Why do you carry a knife?”

“To cut the leashes,” I said.

“But leashes are made of metal. You need a wire cutter. So why do you carry a knife? To kill people?”

“Not leashes bought by rich women, those are expensive, made of fine leather. They can easily be cut with a simple kitchen knife.” Which was what he had there.

He made a fake sound like this made no sense. “How many dogs you stole?”

“Zero,” I said politely. “I brought them all back.”

“You’re a punk kid.” He gave up. “You’ll get what’s coming to you.” And he left the room. The other twenty cops never asked me anything. They continued to stand there as if waiting for backup.

Soon I had to be transferred. Escorted by the lobby of the station house, I saw the potbellied detective again. He was not after me but out to please all these wealthy women. He assured them that I would get jail time. That it was up to them to press charges. They in turn told him they would let their husbands know what a great, great job he had done in capturing that Dogman who had brought so much havoc and destruction to their lives.

The cops took me outside. A mob awaited me. I tried to find my parents, Sal, or Taína in the crowd, with no luck. Lots of yelling, cruelty this, cruelty that. I waited for a paddy wagon to come and take me to the Tombs. One reporter, whom I recognized because I had seen him on television, got close enough to ask me a question.

“How do you feel about your mother?”

“I feel very proud of her.”

“Then why’d you do it?”

“To help. To help people I care about.”

And the reporter looked at me as if this were not what I was supposed to say.

The paddy wagon arrived, and they put me inside it. It drove away, sirens screaming like there was a fire ahead.

At the Tombs’ entrance there was another mob.

“You miserable piece of shit!” Some half-naked woman holding a PETA sign threw a pork chop at my face. I thought it was a waste of food.

Inside, I was placed in a big room, sort of like a little courtroom, and told to wait there with ten other cops who had nothing better to do than guard a handcuffed teen. The wealthy women whose dogs I had borrowed waited outside the big room. Some were even smoking, disregarding the sign, and the cops let them. These wealthy women were angry. They said I had brutally violated them without their consent. I had misinformed them. I had coerced them. Had fooled them. I had not given them the proper information. I had left these wealthy women emotionally scarred for life. They would never be the same again. I had humiliated them, brought shame, and their wounds were so deep they could never continue to live their lives in the same way again.

The women entered. I expected to see my parents. But the cops wouldn’t let them in. The room was large with benches where the rich women sat. I was seated, still handcuffed, when Ms. Cahill walked in and sat next to me. I was very happy to see her. Like all of New York City, she had already heard about the Dogman. She had taken a day off teaching to come to my defense. Ms. Cahill told me not to be afraid. That she was going to speak on my behalf. If these women didn’t press charges, I would be free to go. She said to let her do the talking; it was a matter of making these women see the flip side of the coin. Ms. Cahill had done this for other students, I was sure, because the potbellied detective wanted to speak to the women first.

“Don’t let the real issues here sway you,” he said. “Stick to the facts. Don’t consider things that evoke sympathy or emotions. Leave leniency and compassion to the jury. If you press charges, society will put this man—and make no mistake, he is a man, not a kid, a man—on trial.”

The women nodded and the potbellied detective gave way for Ms. Cahill to speak, referring to her as Megan, so he must have known her.

“The facts are that you lost something you can always get back and you have enough of, which is your wealth,” she said. “All your dogs were unharmed and returned.”

But the women were still angry. It was when Ms. Cahill began to speak with a touch of a poet that the women’s expressions changed. “This is a brilliant kid, far more unique than any of us in this room.” Some women bobbed their heads. “Julio Colmiñares never began at the starting line, like you and I did. He began back there. And yet”—Ms. Cahill dug into her purse and brought out my report card—“he has the grades to get him into college.” She passed my report card around. Some women looked at it and nodded before passing it forward. “In Julio Colmiñares saving himself—he saves all of us.” She walked over to where the women were sitting. “If we intend for our society, our city, to grow, then we begin here, with this boy. You, sweet ladies, are intelligent women, fashioned by a humanist culture that strongly believes that in aesthetics there is meaning. So that in the Met, in the MoMA, in Lincoln Center, in all these things you ladies love, there is not just beauty but transcendence. But what does it mean, finding transcendence in beautiful things, if you cannot find it in yourselves to forgive?” She paused. “And so, sweet ladies, I give this boy to you, and I beg you to give this boy back to us.”

All the women pressed charges.

My rights were read.

I was booked.

Mom emptied out her boot.

She paid my bail.

I went home and waited for my trial.

Coda

THAT NIGHT I couldn’t sleep. While my parents slept like rocks, something told me to get out of bed and look out the window. From the tenth floor down, I saw a demon. A devil standing by the mailbox. The devil was waving at me frantically to come down. To leave my bed and join him that night. Salvador was in full, multicolored costume, with

horned mask, jumpsuit, cape, and everything. I was so happy to see el Vejigante.

I snuck out. Took the elevator down and joined him by the mailbox.

“Where you been?” I said.

“Visiting graves,” he said from behind his mask. I guessed he had had a change of heart and had gone to apologize to those he had hurt, even if it would not bring them back or change the past.

“It’s Labor Day, papo,” he said, removing his mask.

“It’s May,” I said.

“No, not that. Taína.”

My heart began pounding.

“What, what hospital? Where?” I was ready to follow el Vejigante anywhere.

“What hospital, Sal?” Even if my parents would kill me, I was ready to miss school and stay with her until Usmaíl was born.

“Peta Ponce is with her. She said doctors treat pregnant women like they have a disease and not like it’s the most natural thing in the world.”

“She’s giving birth at home?” I was about to cross the street. Head to Taína’s house, where I expected Peta Ponce to be by her side. Salvador saw how anxious I was.

“Relax, papo. Relax and follow me.”

The casita was a shanty built on a vacant lot on 111th Street and Madison Avenue. Once, there stood a Buster Brown shoe store. Where many newly arrived Puerto Ricans and other immigrants from the 1940s all the way to the 1990s would buy shoes on layaway. Next to that store there had once been a botanica. Next to that a mom-and-pop restaurant with a sign in Spanish: IF YOUR WIFE CAN’T COOK, DON’T GET A DIVORCE. COME EAT HERE. All that was left from those bygone times when immigrants came dreaming of their sons hired by the men their fathers worked for, dreaming of their daughters sleeping in the houses their mothers cleaned, all of what was left of that time was the casita. The vacant lot had been cleared and fenced. The shanty had been steadily and firmly erected on that site. It had been painted in bright colors. It boasted four windows and a veranda halfway across the front entrance. A sign hung from the door: UN PEDACITO DE PUERTO RICO. The casita was made entirely of wood, with a large tin-sheet roof. The windows didn’t completely fit the frames, but they served their purpose by opening and closing to let both air and sunlight in. Outside there was a neat garden with rows of sprouting vegetables and herbs. There were roosters and chickens running along with dogs and cats that chewed the basil and mint. Outside the fence, on the sidewalk, was a broken lamppost where a raccoon was sleeping, curled inside where years of rust had created a big hole inside the metal post.

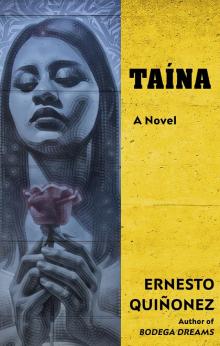

Taína

Taína