- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína

Taína Read online

ERNESTO QUIÑONEZ

TAÍNA

Ernesto Quiñonez was born in Ecuador and arrived in New York City with his Puerto Rican mother and Ecuadorian father when he was eighteen months old. He was raised in East Harlem, also known as El Barrio. He is an associate professor at Cornell University.

ALSO BY ERNESTO QUIÑONEZ

Bodega Dreams

Chango’s Fire

A VINTAGE BOOKS ORIGINAL, SEPTEMBER 2019

Copyright © 2019 by Ernesto Quiñonez

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Simultaneously published in Spanish by Vintage Español, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Quiñonez, Ernesto, author.

Title: Taína / Ernesto Quiñonez.

Description: New York : Vintage Books, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2019. | “A Vintage Books original”—Title page verso.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019010283 (print) | LCCN 2019011761 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984897497 (ebook) | ISBN 9781984897480 (pbk.)

Classification: LCC PS3567.U3618 (ebook) | LCC PS3567.U3618 T35 2019 (print) | DDC 813/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010283

Vintage Books Trade Paperback ISBN 9781984897480

Ebook ISBN 9781984897497

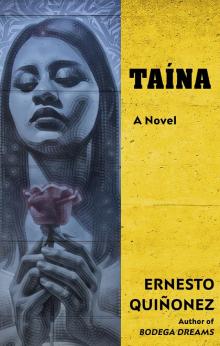

Cover art: “Desert Rose (Nuevas Generaciones)” © EL MAC

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.4

ep

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Also by Ernesto Quiñonez

Title Page

Copyright

THE FIRST BOOK OF JULIO: TAÍNA

Verse 1

Verse 2

Verse 3

THE SECOND BOOK OF JULIO: THE CAPEMAN

Verse 1

Verse 2

Verse 3

Verse 4

Verse 5

Verse 6

Verse 7

THE THIRD BOOK OF JULIO: DOG DAYS

Verse 1

Verse 2

Verse 3

Verse 4

Verse 5

Verse 6

Verse 7

Verse 8

Verse 9

Verse 10

Verse 11

Verse 12

Verse 13

THE FOURTH BOOK OF JULIO: PETA PONCE

Verse 1

Verse 2

Verse 3

Verse 4

Verse 5

THE LAST BOOK OF JULIO: USMAÍL

Coda

Verse 1

AND WHEN AT fifteen Taína Flores became pregnant, she said that maybe some ángel had entered her project. Taken the elevator. Punched her floor. Stepped off and left its body so it could drift under her bedroom door like mist. The elders at her Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses questioned Taína’s mother, Sister Flores, and she vowed that Taína had never been with a man. That she had taught her daughter “Si es macho, puede.” Sister Flores said that she kept so close an eye on her daughter, she was sure that Taína didn’t even masturbate. Her reply had made the elders uncomfortable. They squirmed in their chairs. Though a sin, that couldn’t have made Taína pregnant. The elders inquired about Taína’s cycles: was she early, late, or did they vary? What type of pads did she use? The adhesive kind or the inserted type that are shaped like a man’s organ? By this time all the air had gone flat in Taína’s life, and it was her mother who answered all the questions.

The trial went on for weeks. Every Sunday after service the two women were called by the elders into a cold room. Though embarrassed that the entire congregation was laughing behind her back, Sister Flores stood by her daughter’s story. The elders proposed to take Taína to Metropolitan Hospital to confirm that she was no longer a virgin. Still, Taína and Sister Flores refused; time and time again, they refused. “Dios sabe,” Sister Flores vowed. “I have told the truth.” This left the elders with no choice but to kick both women out of “the Truth.”

Afterward, the two women became an odd sight in Spanish Harlem because they never spoke much. To each other or anyone. In the street they walked hand in hand, mother clutching daughter, and made only necessary visits to the supermarket and the Check-O-Mate for welfare benefits. There were places that the two had never been to, like a movie theater, a beauty salon, or a bakery. The women were living in a universe of two, and it seemed that not even crowds could ever disturb them. Not catcalls from the corner boys directed at Taína: “Mira, ¿to’ eso tuyo?” Not gossip from laundromat women, whose bites were directed at Doña Flores: “Perras cuidan a sus hijas mejor que esa.”

At school, Taína sat alone and got lost among a sea of teenagers. She never cared for clothes, makeup, popularity, or anything. Like her mother, she would smile when smiled at but not talk back, as if her smile were telling you she was not your enemy but didn’t care for your friendship. The boys liked her, they all fell in love with her but soon lost interest when she’d stare at walls or anything in front of her, as if the person talking didn’t exist. The boys called her conceited. I wondered if she knew she was beautiful. It’s not easy to know if you are beautiful. I wondered what else Taína did not know. Did she not know that her voice was a gift? I’d heard that Taína sang beautifully. That she had made the school chorus. That when she took her solo, everyone felt shivers. In her voice was the origin of music. It starts with a cry like that of a newborn. Then the wailing turns, changes, and it seeps inside your skin and drowns out all your pain. In her voice, Ms. Cahill, the science teacher, had said, everyone saw whom they loved and who loved them back. That they could feel their loved ones, smell their scents. That Taína’s voice had woven itself into the fabric of their clothes, that for weeks no matter how much soap or how many times they washed them, echoes would remain. Her voice was fixed into every strand of their hair, too; like cigarette smoke, they’d smell her voice for days. That a black girl had wept and said to Taína that day, “You gave it all to the fire, honey. It was like church.” That’s what I’d heard. And that’s what I wanted. I wanted that sound, that voice, so I could hear love. A sound that people wait their whole lives for. I wanted to see who loved me. But all was lost. And if I remember well, Taína had been in one of my classes. It was biology, and she never sang. She said only one word, “pigeon.” The word sounded hard, as if her tongue had never known sweets, and her accent was pregnant with Spanish, as if Taína had just arrived to the United States.

Shame.

They said it was this bochorno that had turned Taína and her mother to behave like monks, spending their lives locked in a room doing penance. They said it was this shame that the entire neighborhood knew about that caused Taína to stop singing. It was this shame that the two single women were afraid to face and therefore shut the door on everyone and everything. They said Doña Flores had been the worst of mothers. They said Doña Flores should have known better. That even as a child any mother could see that Taína Flores was going to be beautiful and therefore bring trouble. And when Taína’s eyes began to sparkle like lakes in Central Park and her breasts went from thi

ngs boys made fun of to things boys wanted to hold in the dark, this sort of disaster was certain to happen. A pretty young girl like Taína must be kept under lock and key, and Doña Flores was no stranger to men who waited for unaccompanied girls to enter empty elevators.

After what everyone concluded was a tragedy, counselors from our school were sent to call upon apartment 2B at 514 East 100th Street and First Avenue. Doña Flores never answered the door. Detectives made several visits to take the mandatory report. Doña Flores never answered the door. Social workers knocked. Doña Flores never answered. Soon, to cut down on these unwanted visits, Doña Flores pulled Taína out of school. No papers were filed. No homeschooling was used as the pretext. Taína just stopped attending one day.

Doña Flores was now the only one you’d see on the street, and she was either carrying groceries or going to cash in her welfare benefits at the Check-O-Mate. In time, when the gossip was no longer fresh, Spanish Harlem found new things to talk about. Everyone started treating the two the way they wanted to be treated and left them alone.

The only person I ever saw Doña Flores open her door to was this really, really tall old man. He was about seven feet and always wore a black satin cape with a red lining like that of a nurse. He had large hands, and even though he was old, in his late sixties, I think, his hazel eyes flickered like fireflies. People in the neighborhood called him el Vejigante, like the lanky Puerto Rican folk Devil, but nobody knew much about him. El Vejigante had appeared in Spanish Harlem one day out of the blue, as if he had been inside a drawer for many years. He had first been spotted during last year’s Puerto Rican Day Parade dressed as a vejigante, and soon he was living in El Barrio. And just like Taína and her mother, he’d keep to himself. The only time he walked the streets was at night.

Many times I visited Taína’s apartment door. I lived on the tenth floor, in the same project. I’d take the elevator down and punch the second floor. When I’d step out, my heart would race as if I were about to disturb an infant that should be left sleeping. I’d stealthily walk toward 2B, and when I’d get close enough, I’d place my left ear against it. What I heard was complete silence, as if the apartment were empty and ready to be rented out. I kept my ear glued to the door, and when the neighbor in 2A caught me, she said she had done the same and that I wouldn’t hear a thing. That no sounds escaped from underneath the door of 2B, as if not even dead people lived there, for even the dead, she said, made noises.

But I kept visiting her door because I was certain Taína would become like characters in Bible stories. I had this vision of people from all over the world making pilgrimages to Spanish Harlem so they might, just might, get a glimpse of a pregnant virgin living in the East River projects. They’d place their ears to the door of 2B as I had, and if they were lucky, they might be blessed by hearing a sigh escaping from Taína’s saintly lungs. I was so sure this was going to happen. In El Barrio, Taína’s story had spread. Many had shrugged, many had laughed, no one believed, but I felt that it was only a matter of time before 2B in 514 on 100th Street would be known as the building that harbored a living saint.

But this didn’t happen.

The residents of Spanish Harlem continued to believe in the unfortunate shame, the tragedy, that had befallen Taína. The man who had done this was probably the same man whose pictures once splattered the walls of the Hell Gate Post Office on 110th Street and Lexington Avenue. This man had been going around the neighborhood bargain shopping for young girls like one shops for shoes. This man was known to follow unaccompanied girls all the way to their apartment doors. Come up behind them with a knife, demanding, “Your life or your eyes?” This man had brought harm all over the neighborhood, and many believed he was the father of Taína’s child.

But I didn’t.

I believed Taína.

I believed in Taína. And when the man who many said was the father was caught and sent away, I took all the money my mother had given me to buy new jeans and sneakers and caught the Metro-North up to Ossining, New York. I had his name from reading El Diario. I had never visited a prison before, so I naïvely thought that since I knew his name, I could just show up like it was a hospital and say I was here to visit Orlando Castillo and be let inside. The guard told me that I needed an adult who was family to this Orlando Castillo. And that I could come only when the inmate was scheduled to receive visits. I said to the guard that I just wanted to ask the man one question, that it would not take long, but the guard had no time for me. There were tons of families waiting in line to sign in so they could hop on a bus that drove them to the compound. I was holding up the line. The guard told me that I better leave or he would kick my punk ass out.

I left angry because it had been a long and expensive trip, a train and then a bus, but most important I had no answer to my question: “Did you ever visit 2B in 514 and First Avenue? A project in Spanish Harlem by the East River? She is about fifteen, with hazel eyes?” I was sure that that man would’ve said “no,” or most likely he’d lie and say that he couldn’t remember.

I began to question why had I taken so much interest in Taína. Why I couldn’t sleep, eat, or believe in anything that contradicted my true hope that Taína had conceived a child all by herself. Was it believing that she was a virgin, in some way, my idea of keeping her all to myself? Of course I was in love with her. But even at seventeen, I felt something inside me, in a place that I hardly knew was there, tell me that this interest in Taína was more than just a crush, it was more like a sadness one feels for neglected children or books or flowers. A sadness like a coquí that has been told to remain silent and I wanted Taína to sing.

* * *

—

AT SCHOOL EVERYONE would laugh at me, especially Mario De Puma. He’d slap the back of my neck at lunchtime.

“Seventeen? And you don’t know how babies are made, psycho?”

Of course I knew, but Mario was big and I could never win in a fight.

“It was a miracle,” I’d say.

Mario would then take the ice cream from my tray and laugh some more. “The only virgin here is you.” All the other boys looked away, relieved that it wasn’t them Mario was picking on.

Though I was a virgin, I’d respond that sex had nothing to do with it. “Were you there, psycho?” he’d say with a mouth full of ice cream. “Fuck no, right? So how’d you know?”

“Other people were there.”

“Fuck you.” He spat some out on the ground to clear his throat. “Everyone knows you hear things, you hear voices in your big head.”

“I do not hear voices.” Because I did not. I did see things, but they were my way of dealing with my life. The things I saw, my visions, my daydreams, were there for me and only me. “Mario, what about people surviving airplanes falling from the sky? You know? Things that can’t be explained.”

“You sound like such a psycho fag.” And he’d throw what he hadn’t eaten at my face. “I’ve known you since the fourth grade. You thought syphilis was an X-Men.” Mario laughed and walked away.

But I did not care. The ridicule was nothing. I soon began to worry about Taína’s unborn child. I started to save all my allowance, five dollars a week. I began buying gifts for her unborn child. I bought baby shoes, baby clothes, Pampers, baby lotion, talcum powder, baby oil, wipes, baby shampoo. I would leave them at Taína’s door. The next day I’d always find my gifts lying on the cold cement next to the uncollected trash bags.

One day while walking down the street, I saw a secondhand crib in the window of an Army-Navy pawnshop. It was made of beautiful oak with angels carved on the headboard. The crib was a bit expensive and I could never save enough to buy it, so I bought a bassinet that lay next to it. I carried it home, hiding it from my parents, all the while wondering if Taína’s stomach was as round as the moon. As with all my previous gifts, I leaned the bassinet quietly in front of Taína’s door. I

then rang the doorbell and hid in the stairwell like a Halloween prankster. The door opened and my heart jumped. But it was not Taína or her mother, but el Vejigante. This tall old man looked both ways, as if he knew someone was hiding. He then grunted as if smoke and fire could arise from his nostrils. El Vejigante picked up the bassinet, turned it around, rubbed it, and then placed it right back where I had left it and slammed the door shut.

The next day I found the bassinet in the street with the rest of the uncollected trash and junked furniture.

I kept trying, but neither Doña Flores nor Taína would open. I’d knock and place my ear to the door. I’d knock, sometimes politely whisper, “Taína?” or, “Taína, it’s Julio, we were in biology, you there?” And not even an eye would stare back from the peephole. I’d then ride the elevator back up to the tenth floor, feeling as empty as the space between the stars.

Verse 2

WHO OR WHAT is the Thing that orders an atom to join another so as to form a sperm cell and not wood, metal, or air? Who is responsible for the development of a child as it floats in all that goo of darkness? Even at seventeen, I felt God was not the answer. He was too large. Anything could be placed inside Him without really fitting in. What I was after was for someone to explain this miracle to me, to draw me a chart so I could see it down to its most minor of minor details. For it was only there, in the smallest of places, among all that unfilled space that exists between one atom and another, it must be there, where Taína could conceive a child all by herself. What if something revolutionary had happened? What if somewhere in the infinity of inner space, some atom got fed up? What if this atom declared it would no longer follow the laws written in Taína’s DNA? What if this atom started a revolution in Taína’s body? What if other atoms decided they would join that revolution, and instead of creating the cell they were supposed to—created a sperm cell? And as the revolution became more popular, trillions and trillions of trillions of atoms followed suit until the rebellion invaded Taína’s womb by means of self-created sperm?

Taína

Taína