- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

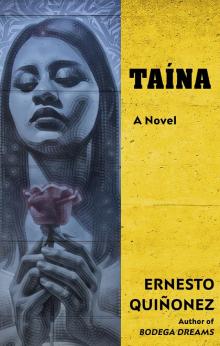

Taína Page 6

Taína Read online

Page 6

And she slowly guided me through el Vejigante’s young life. How much he had suffered, she said. How Salvador was six months old when his father deserted them. His mother checked both into the Casa Isla de Pobres in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. Salvador’s mother worked as a maid for the nuns. They ate together in the same room, mostly boiled potatoes, plátanos, and bread, all served in different variations depending on the day. The casa was a place of locked iron doors and wired fences. Of endless dark hallways and the nuns remaining in the silent background. They were women who kept their eyes low and lifted them only when they needed to punish the orphaned children. It was a silent casa of whispers and hisses, a casa where talking was a disturbance. But at night anyone outside could hear the lunatic screams of those who had gone crazy, the suffering of derelicts, the moaning of the dying, and the sobs of lost and forgotten children. When Salvador turned nine, his mother met a Pentecostal pastor who took them away from the casa and to New York City, where a different kind of trouble started for Salvador.

Doña Flores then looked at the wall again but didn’t say anything back to what or whom she was seeing. She turned to me again. “What happened later in New York City, when he was about your age, in the playground,” she said, following my eyes, which always landed on what I knew must be Taína’s bedroom door. “He was just an ignorant kid. Salvador couldn’t even read or write like a saint. He was a victim. Just like those kids that night.”

“Sure,” I said, “he was just a kid.” Though I didn’t completely agree.

“Like my Ta-te, Salvador has done nothing wrong.”

“How do you know?” I said, no longer staring at Taína’s door. It had taken me all this time to realize that Taína would not come out. Doña Flores was hiding her from me. Her tone told me she knew what I wanted, but I had to give her something first. I did not know what that was. She was telling me things about el Vejigante’s past in order to study me. To see my expressions and draw her conclusion. Doña Flores must have noticed me shaking. I had been dreaming of seeing Taína for what seemed like forever, and all I had was the outside of her bedroom door.

“I knew you were there,” she said.

“Where?”

“At night, behind us, following us. Salvador did, too. You know he only comes out at night.” She held my eyes. “You want to see my daughter?” Slowly nodding like she knew a secret she was not going to tell me. “You want to see Ta-te, huh?”

“I do.” As if saying it would make her tell Taína to come out.

“You want to hear my Ta-te sing?”

“Yes,” I repeated excitedly. And I told Doña Flores what I could not say to anyone, but I knew it was true. “I think I love her.”

Doña Flores did not laugh. She did not say, What do you know about love, you’re just a kid? What are you going to feed the baby, snow? You can’t even sleep without drooling and you are in love? She never said anything like that, which was what my mother would have said. Instead Doña Flores straightened her head, put her coffee down, crossed her arms, looked at the wall again.

“I want to talk to her,” I said, “tell her what has happened to her body, very, very deep inside her body.”

“What, mijo?” She turned her face to one side, showing me only her profile, half lips, one eye, reading me, searching for something.

“A revolution,” I said.

“A revolution?”

I told her what I was sure had happened in an inner space world full of electricity. I did my best to describe to Doña Flores the quantum world I had read in books and seen on TV shows and studied in science class, a world riddled with paradoxes and other dimensions. How inner space doesn’t follow the same rules as those of our big universe. The things that exist in inner space are not tied down to one location or definition. Atoms, which I told her make up everything, live in an inner universe that doesn’t follow the same rules we do. Gravity has no power in their world, neither does light nor speed. I said atoms might even have their own gods. The inner universe belonging to Taína’s body is where Usmaíl is from.

“There was a war in her body—”

Doña Flores cut me off by laughing.

Laughing and laughing. This from a woman who talked to walls, but it was okay.

“Taína needs an ultrasound,” I said, changing the gears, “to make sure the baby is healthy, to check the spine, and Taína needs a Lamaze class for exercise, and she needs—”

“I gave birth without any of those things, mijo,” she said, a bit annoyed. I dropped it because I wanted to be invited back.

She whispered something to the wall again. She waited for an answer and I guess got one.

“Sólo Peta Ponce,” she said to me. “Peta Ponce can bring the truth out. What happened to Ta-te. What happened to Ta-te, sólo Peta Ponce puede.”

“Who?” I said, but she got up and took my coffee cup away. She was going to kick me out soon.

“Peta Ponce. Peta Ponce can make my Ta-te sing again. If you want to see Ta-te,” she said, “Salvador said you could do this.”

“Do what?” I said.

She sucked her teeth, followed by a loud sigh. “Look around, Juan Bobo.” She called me the Puerto Rican name of the village idiot. I looked around but saw nothing but an empty dark living room. Doña Flores rolled her eyes. “Salvador said you could get us the money so we can bring Peta Ponce here. Comprendes, Juan Bobo?”

At that instant I heard the bathroom’s door open slightly. I stood up and looked toward the bathroom. A skinny ray of light shot through, landing on the floor like someone had taken chalk and drawn a yellow line. The line became fatter and through the half-open door I saw Taína. She was wearing a moth-eaten see-through gown. I had never known there was a tiny dark brown mole on her left thigh. With awe I shivered at how her stomach was full, her breasts swollen. I could feel my heart beating. I did not hear music, but I saw circles that made circles that crashed into moons and stars. I saw all these colors, like I had been punched in the eye, triggering fireworks inside my irises. It must have been only seconds, but my eyes managed to take in every detail. Taína turned her head, caught me standing there, ogling at her like a dork. “¡Qué carajo mira, puñeta! ¿Qué? ¿Nunca ha’ visto chocha?” She slammed the door shut.

Verse 7

IT WAS NOT hard finding out where el Vejigante lived. In El Barrio, many had heard about a tall old man who came out only at night. All I had to do was ask around. Soon, I arrived at one of the few remaining walk-ups on 120th and First Avenue. I knocked at the basement’s door, which unlike Doña Flores’s opened quickly. El Vejigante was in shorts, wearing a T-shirt that read: PA’LANTE, SIEMPRE PA’LANTE. He had black socks and was eating a bowl of cornflakes. A skinny old man eating away and happy to see me.

He held the bowl with one hand and shaded his eyes from the light with the other.

“Hey, papo, come in. Come in. Thank you for visiting this viejo.”

The place was a phenomenal dark dump. “You want a knife? A crowbar? I got a baseball bat—”

“No, Salvador.” I called him by his real name because all the stuff he had done was so long ago. “I trust you and you know what I’m here for.” Everything in his tiny basement apartment was fading. The floors were slanted and there were only two windows facing the street above, where you could see the feet of people walking by. The place had a nice lavender smell, though, like some botanicas. A short hall connected the kitchen to the living room, and stacked against one wall were all these books and broken television sets without plugs or knobs. The sets were piled on top of one another and were not dusty, like he must be cleaning them with Windex every day. There was a broken-down sofa and pictures of Puerto Rican landscapes hanging on the walls. But it was the curtains with pictures of kittens, flowers, and saints that told me this was once his mother’s house.

“Hey, you want some beans?”

He put his bowl down, took two steps to the kitchen, and showed me government-issued cans.

“Nah, it’s okay.”

“Hey, I got cheese, I got powdered milk, I can add water and get you a bowl of cornflakes? I got…? I got…? Ham, I can make you a sandwich.”

“No, I’m good.” He had been in prison for years; he must have always been hungry. So I figured he thought everyone else must be hungry, too.

His tiny apartment must have been as big as a whale’s mouth compared with a cell. But it was way better than living with rats and roaches and bedbugs for roommates in a place where lights went out at the same hour. An old wooden piano that took up most of the space stood against a wall, its ivory keys as yellowed as an old man’s teeth.

“You play that?” I asked, pointing at the piano.

“Sometimes,” he said. “You know, music runs in the family,” he said happily, and put the cans down. “You wanna hear something, papo? I can play you something. It’s not in tone, the F key and the E key get stuck, you know, ruins the flats and the sharps, but the rest work well, you know, papo? You wanna hear me play?”

“You know why I’m here,” I said, though I wanted to hear him play.

“The thing about money, right?”

“Yeah, how can you tell them I could get them money when I’m still in school?” I said. “And what does that make Taína’s mother? Saying I have to pay to see her daughter?”

The jewel in his basement apartment was a bright red, white, and yellow vejigante costume. It hung by the closet door like another person was there with us. I recalled that I had seen that same costume in last year’s Puerto Rican Day Parade because it had the same political button pinned to it, ¡Puerto Rico Libre!

“I didn’t lie to you, papo.” Salvador sat down on the musty sofa, his knees almost touching his chest.

“Yes, you lied. I know because I lie to my parents all the time.” I stayed standing, looking at the vejigante costume. The cape and suit were made from the same colorful fabric, while the large mask with horns, lots of horns coming out from all sides, was papier-mâché. I could have sworn the costume moved.

“Mira, papo, I know those women because Inelda is my half-sister.”

“Taína is—”

“My niece, yeah, that’s how it works, papo.”

“What’s Taína like?” I excitedly asked him.

“She’s a kid. She’s like you.”

“Yeah, okay. But what does she like, you know, like to eat?”

“Same things you like to eat.”

“I like pizza.” I shrugged.

“Then Taína likes pizza, too.”

“Okay.”

“Listen, papo, all my sister wants is just a few hundred bucks here and there to cover what her welfare check can’t. Know what I’m saying, papo?” He looked embarrassed, as if he were asking for my forgiveness or that he wasn’t worthy of anyone’s attention. “What Inelda wants is a really nice bed because her back hurts and a television because she likes to watch novelas. But more than anything, what my sister wants is to have this famous espiritista from Puerto Rico come to her house and you can’t pay an espiritista with WIC checks.”

“Peta Ponce?”

“That’s her. Peta Ponce is known all over and she costs a lot of money. She’s the real thing.”

“What you mean?”

“Peta Ponce”—and he crossed himself—“has the power to confuse time. The spirits tell her everything, they lend her the power to twist and transform feelings. You know, bend sadness to happiness, curl shame into love.”

“Wow, sounds weird.”

“No, it’s serious stuff, papo. Inelda knows her, and so does your— You sure you don’t want any food?” he said, walking two steps to the small old refrigerator, which he opened, looked into as if he were proud and happy that he had food, and then closed.

“How does Doña Flores know this espiritista?”

He sat back down, took a deep sigh like he needed it.

“Peta Ponce helped my sister after her pregnancy…and your…” He licked his lips and changed his mind. He kept catching and stopping himself. So I asked again.

“My what?” I said. “My what, Sal?”

But silence fell.

I waited.

I stared at his vejigante costume, his only connection to daylight.

The first time anyone had seen Salvador was during last year’s Puerto Rican Day Parade. He was marching wearing this costume. He was so tall he didn’t need stilts. He marched gracefully and fluidly. This natural, elegant, nimble vejigante would march close to the stands where the people were cheering on the parade, waving Puerto Rican flags. People thought it was a young guy inside that costume. But after the parade was over, Sal took off his vejigante mask and they saw an old man. They all laughed and Salvador didn’t mind one bit, he laughed with the people. The next thing you know, he became a staple in the neighborhood, another eccentric of El Barrio who kept to himself and came out only at night. No one knew about his past. Only I knew, and that was because he had wanted me to know.

“Can’t you just introduce me to Taína? You know I wanna help,” I said.

“I can’t, papo.”

I was happy we were talking again.

“Why?”

“Because you, papo, are the only one who can get my sister money to bring the espiritista to New York,” he said.

“She has you,” I said.

“Me? Look at me,” he said, without a trace of sadness or regret, like he had accepted the cards that had been dealt to him. “I’m old. I’m old and living in my mother’s place, the rent is paid by what’s left of her Social Security. I eat what Uncle Sam gives out through churches. Inelda”—he always called Doña Flores by her first name—“isn’t doing much better than me and she has a daughter who’s pregnant. You all she has, papo. You it.”

As broke as my parents were, there was always food and stuff. Even when my father lost job after job, we didn’t go on welfare. My mother had vowed never to go on welfare. She had always been a proud workingwoman that never had taken a dime from the government. If anything, the government took a lot from her check. But Doña Flores, Taína, and Salvador were pegaó at the bottom of the pot.

“Okay,” I said, “but how much she needs?”

“A hundred dollars here and there, papo. To buy stuff for the baby, get the place ready before the baby arrives.” But for me a hundred dollars here and there was a lot. “And five thousand for the espiritista.”

“You crazy!” My eyebrows shot up. “Five thousand! No way can I get that. There is no way I can get that.”

“Don’t panic, papo. I’m going to show you how. It’s a way to take care of yourself.”

“Okay, how?” I said. “You gonna get me a job?”

“No,” he said.

Just then the costume that was hanging by the closet door fell to the floor. It collapsed onto itself as if it were a skinny man who had lost his skeleton all of a sudden and just crumpled. Only the colorful horned mask stayed hanging, because a nail above the door was holding the mask.

“That hanger is bent,” Salvador said, “it falls all the time.” And he went over to pick up his costume. “The vejigante came from twelfth-century Spain, you know, papo? Saint James defeated the Moors, and see, papo”—and he began to inspect his costume and brushed some dust away—“in Spain the vejigantes represented the Moors. The vejigantes terrified the people, so their only salvation was the Catholic Church or facing the Muslims. When the Spaniards conquered Puerto Rico, we inherited their demon,” he said, “but we embraced the Muslims. We put the Muslims in our parades, we turned the vejigante from something horrific into something pretty great.” And he hooked his costume back on the hanger.

“You’re very smart,” I said. “Why did you kill th

ose kids?”

And silence fell again.

Salvador did not like my question. When he had greeted me, he was like a kid, and now he looked haggard and gaunt like the old man that he was.

“Sorry about that, papo.” He meekly hunched his timid shoulders. Spit gathered at the corner of his mouth. “I forgot what you had come here for.”

“It’s okay,” I said, “I got to go.” I felt stupid for asking him again about that night at the playground. I was tripping him into telling me something he didn’t want to talk about. There was no law that said he had to tell me anything. He had spent years in prison and had done his time. And I felt really, really stupid, too, because there was no way I could get a hundred dollars here and there, let alone five thousand for this espiritista so that Doña Flores would let me see Taína. I knew where my mother hid her money and I planned on stealing it.

“It’s not your fault,” I said. “I just want to help Taína, that’s all.”

“Papo, I can show you how to get the money. It’s a scam. I’m old, but when I was your age, when I was”—and he paused but said it again—“the Capeman, I would run it myself.” He stared at me like he did when we first met, weighing in on if he should tell me anything. His hazel eyes were hard and weary, like he had seen the death of love.

“I only go out at night, papo…,” he said in a docile tone. He had gone to a place that made him regretful. “The daytime…” His face was a flood of tears with no weeping sounds. He sat back on the couch and hid his wet face with his hands. “After what I did that night,” he said, his voice muffled through his palms. “I only go out at night, papo, because the daylight, papo…it shames me. The light shames me.”

Verse 1

SPANISH HARLEM AND the Upper East Side live next door to each other like the prince and the pauper. The Upper East Side’s Fifth Avenue being the Gold Coast. Its streets are aligned with elegant doorman buildings, with movers and shakers and movie stars living in them. Central Park is their backyard. Spanish Harlem is another story. Full of projects, old tenements, and these new but cheaply made expensive rentals where the mostly white young professional new residents live. I could easily walk downtown from my project building on 100th Street and First Avenue and go from dirt poor to filthy rich in ten minutes. I’d walk down Fifth Avenue and see young white girls in summer dresses. Young white boys my age in khakis, white shirts, and blazers with the school’s crest patched on the breast pocket. I’d dream of living their lives. In their buildings, in their neighborhoods, with maybe Taína and the baby at my side. I wanted to know where they were going. What doorman building did they call home? What working elevator carried them to high and wonderful views of this city?

Taína

Taína