- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 2

Taína Read online

Page 2

“¡Ay bendito! Are you hearing voices?” My mother, hands shot up in the air, mouth wide-open, couldn’t accept my explanation. “Pa’ Lincoln Hospital is where I’m taking you. Pa’ Lincoln,” she said, looking up at the ceiling as if God could hear. But God couldn’t, so she looked over at my Ecuadorian father, who could.

“¿Ves? ¿Ves? Silvio,” she said as we sat at the dinner table, “that’s because of you talking of revolutions since he was little.”

“He is a man,” my father said in Spanish, because my father talked only in Spanish. He was already done eating and was now reading the Ecuadorian newspaper El Universo. My father was unemployed. He read all newspapers not just for want ads but for distraction, even read the papers from my mother’s country of Puerto Rico. “He is a man. Leave my son alone.”

I remember feeling proud that my father had called me a man. I wanted to be a man. Taking care of Taína or at least believing in her made me feel like I was acting out my role. Who or what had given me this role? I didn’t know. But just like those Buddhist monks who couldn’t explain what nirvana was, they just knew when they had reached it, I knew this was what I was supposed to do.

My mother sighed loudly. She turned on the kitchen radio, low volume. She used to be a salsera but now loved songs from bygone times. Tito Rodríguez sang, Tiemblas, cada vez que me ves.

And then she faced me again.

“Julio, Taína was…touched.” My mother could never say certain words, as if saying them would make their definitions enter our home.

“I don’t believe that, Ma.”

“He is now eighteen, he is a man,” my father repeated without missing a black letter on the printed page. “Either take him to the hospital or let him make up his own world.”

“See, Ma.” I nodded and pointed in Pops’s direction. “He gets it.”

“Tu pa no sabe na’ ”—she paused—“because you’re not eighteen.”

“So, almost, seventeen and a half—”

“Oh, big man,” Mom said, inflating her chest.

“Leonor.” My father placed the newspaper down for a second. “You took him to church. You told him that one man, just one man, ruined the perfect plan of God. So, believe Julio and his revolutionary atom.”

“Oh, entonces”—she crossed her arms—“you believe in Julio’s revolutionary atom?”

“No. But I do not believe that you came out of my rib either.”

“That’s different,” Mom snapped, “Adam and Eve were real! La Biblia es verdad. What Julio is talking about is crazy talk. That’s how crazy people talk.”

“He is in love,” Pops said, and it embarrassed me. “That is all. My son is in love.”

“No, I’m not,” I lied. “I don’t like Taína. I like older girls,” I said, as if I had to convince myself.

“No, señorito, love or no love you better leave those women alone. I knew Taína’s mother, esa Inelda está loca. ¿Me oyes?”

“Yeah, yeah, Ma, I heard, I heard, she used to be a great singer and went crazy, you told me. You two were friends before she went crazy, I heard. And I’m not in love, okay?”

“So, you’re not in love, eh?” My mother pointed at my food.

My father looked at my full plate.

“You take after your mother,” Pops said. “Out of all Latinos, it is Puerto Ricans.” Pops picked up the newspaper that lay aside on the table. He flipped through El Vocero and laughed. “Look at this, you Puerto Ricans believe in Chupacabras, aliens in El Yunke, espiritismo—”

“Oh sí, pero ¿quién lee eso? So you must like it,” Mom said, ripping the paper from his hands and rolling it into a cylinder. She then hit Pops over the head with it.

Pops laughed, looking at the rolled-up newspaper.

“Leonor,” he said, “you would have made a great union buster, the way you handle that newspaper.” Mom made believe she was about to whack him again, but she smiled lovingly.

“Now, in my country,” my father said, looking my way, “you had to choose sides and stick with that choice.” My father was really talking about his youthful communist days in Ecuador, but I could place what he said only in context to what I was going through in my own life. I had chosen to believe that Taína was telling the truth. I would not go back no matter what common sense was handed to me. There were things that took time to be understood. All I had to do was hold the fort until something or someone would come and help me in helping others understand what had happened to Taína.

“Okay, basta,” Mom said to my father. “Tú me vas a dar un patatú.” Mom then looked my way again. “And you”—she pointed a forefinger like God as she opened a kitchen cabinet and took out the Windex—“you better not get me in trouble with my elders again. You better stop going down to the second floor and spying on those women and that crazy old man.”

“I don’t know that old man,” I said, “I don’t know anything about el Vejigante. I just think Taína is telling the truth.”

“Well, she’s not, and I don’t like that Taína.” She squeezed twice, and Windex spat on our glass kitchen table. “And that old man, no one knows anything about him because he must like it that way and that means he is hiding secrets,” Mom said, waxing the glass clean.

Y por eso tiemblas…Tito Rodríguez sang.

When my mother said the word “secrets,” my father’s eyes left the newspaper and shot them at her. He was telling Mom something and she didn’t want to hear it, so she didn’t look back at him. I knew their games of dealing with each other, and at times it made me mad so I just let it be.

“Those people are hiding secrets, Julio.”

“You don’t hide secrets, Ma,” I said. “That’s like a double negative or something?”

My father cleared his throat and seriously continued to look at my mother. “We know about things,” he said, “things we hide.” Whatever he was referring to, Mom did not like it. She wanted to say something back but jailed her tongue. He stared at her intensely a bit longer, and when she didn’t say anything, that was enough. He won. Whatever it was, Mom did not want to go there, wherever it was that Pops was headed. So she continued to polish the kitchen, singing along to Tito Rodríguez’s smoky “Puerto Rican Sinatra” voice. Together they sang the story of a woman who trembles when she sees the singer, and why does she continue to hide that she is part of him?

Verse 3

IT HAD BECOME a habit. I’d wait for my parents to go to bed and then sneak out of our apartment. Out by the lonely hallway I’d punch for the elevator. Wait. Get in. Step out and open the project’s entrance doors and go out onto the sidewalk. I’d then cross the street and face our building, but instead of looking up ten flights to find my bedroom, I’d simply gaze up at Taína’s lonely second-floor window. I would lean on a blue mailbox and see Taína’s shades drawn, the lights always low. I’d stand there long enough to see many of our project’s windows go black.

One fall night as I leaned on the mailbox, staring up at Taína’s window from across the street, I saw two silhouettes step out of our project. It was late and dark, but I could see a fat figure holding on to the skinnier one with this grace and I knew it was Taína and her mother.

My heart jumped like a dolphin.

I hadn’t seen Taína and here she was. It took all my strength to not cross the street and scare them away. I wanted to be near Taína, but I feared that if her mother saw me, they’d go right back up. What were they doing out so late? Where were they going? Maybe Taína needed her exercise, I thought. Maybe she needed to stay healthy so she could have a good birth. This was how she must get fresh air, I thought. Taína must come out at night so no one bothers her. No one sees her. The two women had shut themselves off from the rest of the world, and like owls they felt comfortable flying when everyone else was asleep.

From across the street I saw Taína’s semi-brown

semi-blond hair was frizzed like she had just gotten out of bed. Her hair hinted at being charged with electricity and there was a static glow rising from her frizz like a halo. Her coat was woolly and oversize, as if out of impatience she simply took the first one at hand. Her coat was a cloak, like she wasn’t so much cold but needed something large to hide inside of. I followed behind all the way from 100th Street and First Avenue to 106th Street and Third. Once we left the enclave of the projects, the night came alive. The new residents of Spanish Harlem had come out to take in all that new nightlife. There were lots of bars and cafés opened till late where all these young, mostly white people ate, drank, and laughed in what they were now calling Spa-Ha. But even among the new residents I didn’t lose sight of the two women. From across the street I saw them turn the corner. He had been waiting for them, standing tall as ever, wearing his black cape and carrying a walking stick. El Vejigante kissed both women on the cheek twice like Europeans and hugged them like he was their father. They spoke for a few seconds before continuing to walk, casting this strange wide shadow like misshapen squares. They didn’t walk but rather strolled like they were taking in sun in Central Park and not out past midnight. At times I could hear Doña Flores laugh a little at what el Vejigante was saying. Soon, all three went inside a twenty-four-hour bodega. I crossed the street, and from outside the bodega’s window, I saw Taína pick up a glossy magazine and her mother some nail polish remover. El Vejigante didn’t look at anything and just waited by the cash register. I shifted my weight and squinted my eyes to see what the title of the magazine was that Taína had picked up, but I couldn’t read the cover. I soon realized that it wasn’t nail polish remover but agua maravilla that Doña Flores had gotten. At the counter, Doña Flores placed Taína’s magazine, the witch hazel, and a pack of Twinkies Taína had wanted. El Vejigante flipped his cape aside and dug into his pocket. He didn’t seem to have a lot of money because he paid in coins, like he had broken his piggy bank. After that, I hid behind a parked car as all three left the store, and el Vejigante must have asked Taína something because she nodded and smiled.

Walking, Taína no longer held her mother’s arm. She unwrapped her Twinkies. Taína ate them in big bites like they were hot dogs, and after licking her fingers clean, she began to walk slower as she flipped through the pages of her magazine in a way that let me know she was only looking at the pictures. Maybe because it was nighttime she couldn’t read, but after three more blocks, she was done and she gave the magazine to el Vejigante, who took it and rolled it up nicely as if he didn’t want to ruin it. Taína held on to her mother once again and the two continued to walk side by side.

Third Avenue was lit by its lampposts and the late fall night was cool. When they reached the playground on 107th Street, Taína and her mother walked inside, but el Vejigante did not. He waited outside the gates of the playground as if he could not enter because he had been forbidden to cross some invisible line. He simply stood outside the playground’s fence, not even sitting on the benches, standing as if he had been a dog left tied to a parking meter. Taína then chose a swing, and even though her stomach was big she sat on the swing with no problem. Doña Flores began to push her from behind so Taína could gather more speed and her swing could climb higher. It was then that I heard Taína playfully yell at her mother the word “sí.” And I was so happy to have heard Taína speak, and I became afraid that some act of God or something might interrupt this moment by taking me away. I started to sweat, but then, all of a sudden, this anxiety left me and some mysterious change came over me as if I knew everything was going to be all right.

Doña Flores kept pushing Taína’s swing. Taína’s legs were dangling and she’d bend them down and then straighten them up to gather speed while holding on tight to the swing’s chains. Taína threw her head back, letting the wind take hold of her hair, and then I heard Taína speak again, “No.” Two words. I knew Taína could sing beautifully and maybe she would right there and then. A cappella was just as good. I was so excited knowing I would see who loved me or maybe even have one of my visions. But her swing soon came to a halt. Her mother asked her something and Taína nodded, and the two women left the playground to rejoin el Vejigante outside the fence.

I was a half block behind when they turned toward the East River and back toward home. El Vejigante continued to walk like he was on a stroll, though the two women were now walking with their heads down, making sure no one saw them. Even this late, even with the streets this empty of native residents and mostly filled with young white people, they began to walk without making eye contact with cars, lampposts, mailboxes, buildings, or anything.

In no time, all three reached our project building on 100th Street and First Avenue, and all three went inside and I was alone again.

I was happy at having been so close to Taína, and it had taken all my strength not to yell, “Hi.” I looked around at the wall of projects surrounding me. I smiled because among all those square windows that lent the projects its definitions, inside one of those cubes lived a saint. And then somewhere underneath uncollected garbage bags, I heard a cricket calling out for love. I looked down at the concrete and felt like all the garbage bags, the candy wrappers, coffee cups, oil slicks, broken glass, gum stains, cigarette ends, pizza boxes, all the cans, all this garbage, were telling me that these things loved me. I belonged to them. That even though I was from the projects, this world could still love me, embrace me, and make me feel valuable and not like an unwanted child.

And then it brought me comfort to know that all these buildings full of poor people lived close to a river. A real river, the East River, and for some reason I started to walk toward the water. When I reached the East River, I realized for the first time how only the FDR Drive divided the projects from the water’s boardwalk. The cars on the highway sped by me, sounding like waves.

“Don’t be afraid, papo.” El Vejigante startled me. He held a crowbar in one hand. I slowly backed away. I was ready to run when he caught my eyes looking at the iron. I sensed he felt embarrassed.

“Take it.” El Vejigante held the crowbar out toward me. “Take it, papo.”

I snatched it from his hand, though I knew I could never hit him. I held the crowbar like a baseball bat that I was willing to swing at any moment.

“Now I hope you’re not scared now, papo?” he said with his hands in front, in case I did swing. He was old but tall; it gave him the appearance of having a lot of life left in him. He was light-skinned, and it was in the way he called me papo that I knew he was one hundred percent Puerto Rican, like my mom.

“Many people don’t know me because old people are invisible.” He laughed a little laugh. He had a huge gap between his front teeth. Being close to him, I saw that his cape was worn out, the satin fading. His pants were thin, as was his shirt, the fabrics disappearing into strings. His hair was long, split in the middle, and held together with a rubber band. That night when I first talked to him, he reminded me of a broken-down Jesus Christ, ragged, old, and fallen, whose disciples had long ago deserted him.

“What you want?” I said, though what I wanted was to ask him about Taína.

“Me?” He slouched the way tall people do when they feel inferior for being so tall. “Me? I’d like to begin again. But you see, you can’t do that, papo.”

“Okay,” I said, because I didn’t know what he was talking about. I gripped the crowbar tighter just to give me something to do.

“You’re Julio, right? You live in Taína’s project, like eight floors up?” he asked, and I nodded. “I’ve seen you around.” His voice was all gravel like those fancy coffee machines.

“So what?” I said.

“No, it’s good. You believe Taína is telling the truth—”

“She is telling the truth,” I interrupted. “You know her, so you know she is telling the truth.”

“Okay, okay, okay, calm down,” he said, be

cause I didn’t know I had raised my voice.

“I’m sorry”—my voice lowered—“are you Taína’s father?” Though he was too old to be, I asked.

“No, no, no. No.” He crouched, hunching his shoulders like he was humbling himself. “You want those women to talk to you, papo?” And though his hazel eyes still sparkled, his face was riddled with wrinkles.

I shrugged like I didn’t care.

“Don’t be like that.” He knew I was playing it off. Trying to be cool about it.

“I don’t trust you,” I said. It was late, and I needed to get home before my parents woke up.

“I don’t blame you. Trust is hard, papo, but okay,” he said. “Meet me tomorrow night, papo. Same time, across from Taína’s window by the mailbox, and I’ll tell you what to do. I’ll tell you what to do so they can open the door, okay?”

I nodded.

And he turned around, about to walk away.

“Hey, you want your crowbar back?” I said, and he turned to face me again.

“Yeah, I might be able to sell it.”

“Vejigante”—I gave him back the iron—“what’s your real name?”

“Me?” He took his crowbar and looked up at the night sky, as if he could find his name in the stars. He then looked down at the concrete, then at the highway of cars passing by, then at the night sky again, as if he weren’t sure where to start or what to say. When he did face me, his hazel eyes were huge, like an Egyptian’s eye in those mummy coffins at the Met. He scanned my face like a nervous radar, debating if he should tell me.

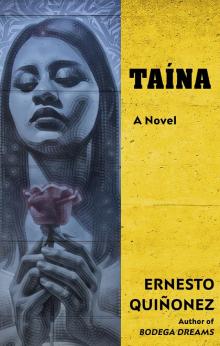

Taína

Taína