- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 11

Taína Read online

Page 11

“Or not go and say you went. So I am going with you, y se acabó,” she said, and then headed over to the stereo to play her new José Luis Perales CD.

Quisiera decir / Quisiera decir tu nombre…

My father closed the refrigerator.

“I know what to cook,” he shouted in Spanish. “I am going to go out and get the ingredients to make seco de chivo.”

Ecuador’s version of Puerto Rico’s asopao.

“I hate that, Silvio.” My mother forgot about humming. “I don’t eat deer. You better not go out and buy venison.”

“You ever tried it?…No? So how do you know you will not like it?”

“Ay bendito, I don’t need to have a hole in my head,” Mom said, “to know I don’t want a hole in my head.”

“I am going to make it anyway,” he said. “And seco de chivo is just the name. It does not have to have venison, it can be made with chicken.”

“I don’t care,” Mom said. “I’m not serving you.”

“Fine,” he said, “me and Julio will eat, and I will serve us.”

They both looked my way.

I was to choose who was right.

Once my father lost his job, cooking became the only power he had in the house. Mom brought in the money and now I was bringing in money, too. My father wanted to make this Ecuadorian dish because it was his way of saying he had some control in this house. They were both the same people, I thought. My mother loved Puerto Rico, but that was the past, and the closest thing to it was Spanish Harlem. But my father never felt this way about New York City. It was the Ecuador of his communist youth that sustained him.

The day would come, my father liked to lecture in Spanish at the dinner table, when the New Man will be born and bring with him a New Order where all rent collectors and welfare pimps will be hanged by their underwear, he’d say, sounding like Fidel Castro. As a little kid, it was a day I, too, awaited. When would it come? I knew no rent meant more money for us to spend. Maybe more money for us to buy fresh meat and not have to eat leftovers day after day. Maybe money for me to have a second pair of jeans, a second pair of sneakers, and, if anything was left over, maybe a movie. My father’s communist pamphlets were full of pictures of happy and strong men working the harvest, their busty wives bringing them water, apples, and bread as little kids like me picked flowers. Above us a smiling Red Comrade Lenin provided in abundance for all.

Es Jehovah, my mother would counter, that will destroy all the wicked people and turn the earth into a paradise. A New Order will come, but by Jehovah. As a little kid, it was a day I, too, awaited. When would it come? My mother’s Watchtower magazines portrayed that glorious paradise with these colorful pictures of happy and strong men working the harvest, their busty wives bringing them water, apples, and bread and little kids like me playing with baby tigers, baby lions, baby zebras, and eating all the fresh fruit they could munch on. Above us the hand of an invisible Jehovah provided in abundance for all those on earth.

My parents met not here but in Panama. My dad had been kicked out of Ecuador for being a communist. They don’t kill you in Ecuador: they give you a one-way ticket to anywhere in Central America. He chose Panama and not Nicaragua because a revolution in Panama was still possible, while Nicaragua was like operating on a healthy person. There he met my mom. She was on vacation with her parents. She was more depressed than a weeping willow. Her parents thought it might do her good to leave the country and take in some sun. Or maybe it was because of the shame that the Bobby singer incident had brought them; they just wanted to forget the whole thing had actually happened. I never really knew. All I know is she saw this commie punk who, family legend has it, saw her and sent her a note: “Cuando te ví flores crecieron en mi mente.” And that was the beginning. My mother loved bad boys, and she actually thought that my dad was one because he had been thrown not just out of a bar but out of an entire country. She couldn’t have been more wrong.

My father, like most Latin American communists, just talks a good revolution. My father considered the United States the enemy. The capitalist who will rip the tusk of the last elephant in Kenya for a two-bedroom in East Hampton, he’d say. They will cut down the last rubber tree in Brazil for a Diners Club card. They have no friends because they have subscribed to the law of dog eat dog and will eat one another should the stock market allow it. My children will be born not under a capitalist green sky but under a blue one, he’d say to her. The thing was that my mom was hot. She still dyed her hair blond and wore the green contact lenses, tight dresses highlighting more curves than an American highway. And she told him about this place in New York City, where everyone spoke Spanish. There was no need to learn English. He could find a job easily, as he had an engineering degree from the University of Guayaquil. That magical place was El Barrio. In Manhattan. So they got married, and by the time my father found out this was not so, that his degree from Ecuador was useless, that he needed to learn English, and that jobs were not that easy to find—I was conceived.

“I’ll eat it,” I said, to make my father feel good. “I’ll eat the seco de chivo.” He did cook, after all, and I’d try it.

“Disgusting,” Mom said. “I’ll go out and get some food. Rice, gandules, pasteles, chuletas, pechuga de pollo, you know? Normal food.”

“And what is normal food?” my father asked.

“What I just told you.”

“That is normal for you, but in China—”

“We’re not in China,” she said. “I want normal food.”

My father decided not to argue. He huffed and puffed. He went to put on his shoes. The new lapdog I’d borrowed was lying on a pillow bed next to them. Without saying a word to me, my father took the leash and put it on the dog. I wanted to tell Pops he couldn’t take the dog, but my father was mad. He also thought by walking the dog and shopping, he was killing two birds with one stone. So I let him. I went to my room and picked out clean clothes. When I was all dressed, I picked up Taína’s iPod, books, and magazines. On my way out the door, I saw my mother looking at herself in the bathroom mirror. The earrings dangled from both sides of her smiling face and she was humming. Quisiera decir / Quisiera decir tu nombre.

Verse 7

WITH AN IPOD, a gallon of ice cream, groceries, Blow Pops, Starburst, bedsheets, books, magazines, and biodegradable diapers, because I had read plastic diapers hurt the environment, and with an envelope full of money, I knocked. I no longer had to wait.

“Come in, papo. Come in.” It was Sal. “This is not my house so I can’t offer you food, you know?”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I already ate.”

“Us, too. I mean if I knew you were coming…Next time, next time, okay, papo?” And he helped me stack up the diaper boxes against the wall and took the groceries to the kitchen.

There was a brand-new flat-screen television hanging on the living room wall. It was tuned to Telemundo. A variety program where there was a scantily dressed woman bending over to fill a cup of water from the office water cooler. A man was trying to make copies nearby, and when his eyes caught the woman’s ass, the Xerox machine started ejecting paper everywhere. The laugh track volume was really low, as if Doña Flores didn’t want any of the neighbors to hear that she, like many Latinos, liked this kind of humor. It’s old humor. Slapstick with very little intelligence, but that’s what our parents liked to watch. I saw that the couch was draped in blankets and pillows. At first, I thought it must be where Salvador had slept the night before. But I soon realized that it was really where Doña Flores slept, as this was a one-bedroom and Taína had her own room. I looked for Taína. The door to her room was closed.

Salvador went to get his half-sister. She was in the bathroom and he knocked. When Doña Flores came out, she was glowing as if she were the one that was pregnant. The first thing she asked for was the money. I gave her the envelope. Doña

Flores’s eyes became moons. She didn’t ask how I or my mother was doing. Nothing. All she said was, “Juan Bobo, Ta-te está en su cuarto. Sólo toca antes de entrar, ¿okay?” And Doña Flores and Salvador sat together at the kitchen table. They budgeted the money as they talked quietly about Peta Ponce.

I had never seen Taína’s bedroom or any girl’s bedroom, and I didn’t know what to expect. When I gently knocked and said my name, I heard Taína’s agitated voice, “¡Coño! Now I gotta put on clothes. Wait!” And with ice cream and books and magazines in hand, I nervously waited. “Fine. Come in, dummy,” she said from the other side.

I opened the door and walked in. I didn’t close the door all the way, leaving a ray of light to guiltily escape from her bedroom and into the living room, where the television stayed on.

Taína’s room smelled of baby talcum powder mixed with some sweet, lowly scented peach soap. Her walls were not pink, like I had thought all girls’ rooms were, but an off-white, like moths. She had no posters of movie stars or kittens or puppies or anything other than a mirror on the wall. A multicolored rug covered most of the floor, and her dresser was a dark crimson that matched her sheets, comforter, and pillows. The crimson was a good color, I thought, because dark red hid spots and dirt. I always drooled when I slept, and so I had red sheets, too, to hide my drool.

Taína looked at what I was carrying. She went not for the ice cream or the magazines but for the books. She took them off my hands and slowly sat her pregnant body back down on her bed. Her back leaned against the headboard, where she had placed a pillow to hold herself up. She patted the side of the bed next to her, commanding me to sit down. Her bed was a frightful mess of Cheetos crumbs, Doritos, popcorn, and chips. I wondered, Where were the roaches? They must love her as much I did. I nervously sat next to her. I felt our thighs rub against each other on the bed. My circuitry exploded, and yet it felt as natural as breathing.

“You dummy, you stupid idiot, take your shoes off. Don’t dirty up my bed.” She took the Blow Pops and thought about having one but had a Starburst instead.

The bed was full of crumbs, so I didn’t know what she was talking about. But I took my shoes off anyway and placed them neatly on the floor and sat beside her again. Taína had thrown a T-shirt over the same gown she always wore, but this time it had fewer wrinkles, as if it were a new one. The gown covered her legs but not her lovely feet, whose thick ankles were full of water. It would be only a few weeks before Usmaíl’s arrival.

“I like your room,” I said. Taína shrugged. She continued to read the books’ jackets. Her lips barely moved, as if she were silently praying. There was a glow behind her like in paintings of saints at the Met. I don’t want to sound dumb, but I saw it. It was a golden glow that hovered around her head as if there were a light behind Taína. But then the glow dimmed and faded.

“These books are fucking great!” She pressed them to her breasts as she crossed and uncrossed her legs that lay on the bed.

“Do you want ice cream?” I said, because it would melt soon if she didn’t put it away. “I brought you ice cream. I got ice cream—”

“No, I don’t want fucking ice cream. Did you bring me gum?”

I forgot.

I panicked and she knew it. Taína exhaled and shook her head.

“It figures. Can’t you do anything right? Next time you better freaking bring some.”

So I placed the ice cream on the floor next to my shoes and I gave her the iPod. I told her that I had already connected it to the Internet Wi-Fi we have at home and all she had to do was create her own account and stream all the music she wanted.

“Really?” She was excited but didn’t believe me.

“Yes,” I said.

Taína knew how to work the iPod. She quickly made an account for herself and smiled as she typed it in.

“Want to know my password?” she said. I nodded. “Okay, it’s Bigbichos2000.” She was trying hard to hide her excitement and not laugh.

“Good password”—not knowing what else to say—“hard to break that one.”

Having music in her house again made her happy. And for two seconds, she hummed. It had a nice melody and it was as close to hearing her sing as I had gotten. I think she wanted to hum some more, but she seemed nervous. She then hid the iPod and earphones under the mattress. “Mami can’t see this.”

“Why?” I said. “It’s only for music, really.”

“She says that music disturbs the spirits.”

“Oh.”

“Yeah, she says that the spirits will be confused and forget what happened to me if they hear music.”

“You think that’s true?”

“Well, if it is, then those are some really fucking stupid spirits,” she said. “But I don’t want to get Mami upset. I’ll listen when Mami is asleep.”

And I let that go.

Taína went back to her books.

I had brought her Under the Feet of Jesus, Caramelo, When I Was Puerto Rican, and How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents. Taína couldn’t have been happier, but when she saw the book about the universe, her eyes shot up at me.

“What…the…fuck…is this shit?”

“It’s the origin of us,” I said. “I mean all of us, everything, planets, the sun, other galaxies, everything. How it all started.”

Cosmos was a big coffee-table book with colorful pictures of nebulas and galaxies and told of the birth of the universe. I had looked at it many times in the school library. I liked the pictures. But what I really liked was how it explained everything in easy and common terms. It talked down-to-earth in a language that everybody could easily understand.

“See, Taína”—Cosmos made me feel and sound smart—“the universe, like Usmaíl, created itself, too, see?” She began thumbing through the pictures. “It’s like what’s happened in your body. One atom asked another atom if they could join and that atom said, ‘Yes.’ Sort of the way the universe began with the word ‘yes.’ There was nothing, just these particles floating, and then one particle asked another particle to join and that particle said, ‘Yes,’ and boom, a big bang. It just happened. In the beginning was the word. But the word was ‘yes.’ See, no need for a Father, or a God. Or anything. Just a yes.”

“Yes,” Taína said, sneering. “Yes, if you ask me if this book fucking sucks? Yes.” She threw the book aside. “And don’t bring up that stupid revolution, please. I already threw up today and I’ll kill you if you make me vomit again.”

But I still told her about the universe becoming sentient out of a dead nothing. What had happened to her was something similar. How long ago all these proteins and amino acids floated in goo, in some womb-like ditch here on earth millions of years ago. We came out of those slimy puddles, just like babies do.

“Where’s a picture of those fucking puddles?” she demanded, opening Cosmos again. I think this got her attention, as she thumbed through the pictures more carefully. I examined her small hands and saw her grubby fingernails. But the dirt stuck between them did not matter to me at all.

I showed her the picture of a young, volcano-like earth and told her the puddles were there.

“No way.” She pouted. “I don’t see shit.” She closed the book. “I’m getting bored and you didn’t bring me gum. And your shoes did dirty my bedcovers, you dummy, you stupid idiot.”

“Listen, Taína, a revolution was fought inside your body, okay—”

“Okay nothing. Stop!” She exhaled loudly and her stomach rose like a mountain. “That is why Mami wants that Peta Ponce bitch to come over, okay? The espiritista helped her after I was born. I know all about it, okay? What Mami did to herself.” I knew what Taína meant. Sal had told me. It was then I realized that things like this are easy to repress. They are so horrible you do your best to forget them, and soon, you fool yourself into thinking that it never happened. �

��And Mami says the espiritista will help me, too. She will get the truth out of me.” And tossing Cosmos aside like a dirty diaper, she said, “And I know, Julio, that that stupid espiritista bitch ain’t gonna say shit about some stupid fucking revolution fought inside my body, okay? So fucking drop it.”

“How do you know Peta Ponce won’t say anything about a revolution in your body?”

“Because I know.”

“How do you know?”

“I just know.”

“How do you know?”

“Because I just fucking know!”

With not too much trouble Taína got up from the bed and stood in front of the mirror. “What I know is that this thing in my eye is killing me. Come over here,” she ordered, and tilted her head back, prying her left hazel eye open to try to get rid of a speck of dust. “Blow on it, gently….Not so hard, you dope,” she said.

I nervously held her warm temples gently and stood face-to-face. I was seven inches taller than Taína’s five feet one inch and I was looking down at her saintly eyes. “Bastard is there”—her eyes wiggled—“I can feel the fucker….” I gently blew on her rolling hazel eyeball. “Easy, easy, you dummy, you stupid idiot. Easy.” Her body tensed up, only to slacken once again. Then her adorable lips parted. I felt the heat of her round stomach against mine. Then my lips touched the dry, rough corners of hers with a tiny quick peck until with an impatient wriggle my lips pressed onto Taína’s lips. And the world became new.

I tasted Cheetos in her saliva mixed with lemon Starburst.

Taína pulled back and wiped her lips against my shoulder. Her cheeks were flushed, her lips were still glistening, and she brushed a strand of hair aside. I braced for an insult.

“When Peta Ponce comes,” she said nicely, “I want you to be there, okay?”

“Okay.”

“Promise.”

“Yes.”

“No, you better promise.”

“Yes, yes, I promise,” I said.

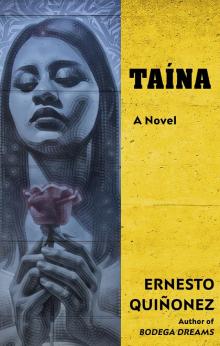

Taína

Taína