- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 12

Taína Read online

Page 12

“Okay, good.”

She held the door open for me.

“That was nice,” she said. “That was very nice. Fucking awesome, actually. And thanks for the iPod. I can’t wait till Mami is asleep. Bring me Twinkies next time, okay?” And she smiled a tiny smile, shot me an air kiss before closing her bedroom door.

Verse 8

“SHE WAS WALKING aim-less-ly in Central Park,” I said, and the dog owner saw little Ralphy wailing. “Our little brother loves her, but when we found out she was lost, we brought her back to you.” This time the lady went for the reward right away.

“You get him a dog just like Mrs. Dalloway,” she said, though that was my line, and she didn’t even wait for little Ralphy to cry on BD’s fake arm.

“It’s a pure Cavalier King Charles Spaniel.” She said a name that sounded expensive, but I simply thought that it looked like the dog in the Disney movie Lady and the Tramp. “This should be enough to get one just like her. You’ve no idea how happy you have made me,” she said, kissing her dog, who barked a quick thank-you to me for taking care of her. We exited the doorman building a block away from the Guggenheim Museum. This reward was big, and I had now opened up a bank account. Had gotten the forms, and though my mother had told me not to trust banks, she still cosigned at Banco Popular on 106th Street and Third Avenue. I now deposited all the reward checks there. I gave BD his cut, gave Sal some, Mom some, gave my dad some, hid some inside Mom’s boot without telling her, and gave the rest to Doña Flores.

I brought Taína gum and Twinkies.

“These are bad for you,” she scolded me. “You want me to get fat? I can’t fucking believe you. Don’t you give a fuck about me?” she said. I didn’t know if she was joking because she was fat, she was pregnant. But she kissed my cheek and I was happy. Doña Flores was asleep in Taína’s room, so without asking, I placed my hand on Taína’s stomach. Touching her stomach was a sensation that I knew was not going to come back. It was as fleeting as the life of soap bubbles. Once Usmaíl arrived this, too, would be over. So I kept my hand on her stomach, feeling Usmaíl kicking. Taína slapped my hand away. “Okay, stupid, what the fuck, enough, you wanna play patty-cake with the baby? God.” But then she took my hand and led me to the couch. The television was on.

“Rub my feet.” I didn’t know if I heard that right. “Come on, what are you waiting for? Rub…my…feet.”

I was paralyzed with happiness. Taína turned her body toward the edge and lay back against the couch’s arm, her moon stomach now facing the ceiling. She placed her feet on top of my lap at the other end of the couch. I took one foot in my hands and it was warm. It hinted of body lotion mixed with mothballs. I wanted to kiss her foot.

“I don’t know how to do this,” I said shyly. But Taína’s eyes were closed as she made a moan of half-pleasure, half-sleep. Taína squirmed a little. The more I massaged her feet, the more she squirmed and the higher her gown would ride up on her. My clothes felt so miserably tight I thought they would break out. I took full advantage in studying her bare legs.

“I want more books, Julio,” she said with eyes still closed. I was happy to hear her voice, as I did not know where I was at the moment or what part of Taína I was looking at. “I liked the one about the farmer workers. I liked Estrella. That Viramontes book was good, the others kinda sucked.”

“I’ll get you more,” I said, checking to see if her eyes were still closed. I kept tabs on her gown continuing to rise above her knees. I soon recognized the tiny dark brown mole on her thigh from that first night.

“You better fucking get me more.” Her hair sprawled as her head was resting firmly against the couch’s arm. “I’d love to go places, Julio.” With her eyes still shut, her hand found her lips where she had drooled, and she ran her wrist across her mouth.

“Where?” I gently squeezed and pressed her feet, heel, ankle, and calves. Her bare knees kept slowly knocking against each other.

“Places. I would love to see places. Have you been places?”

“Just Puerto Rico and Ecuador.”

“I would love to go to Puerto Rico. Mami says it’s paradise.” Squirming and then yawning. “I hate being by myself. I wish Usmaíl was here already so I’d have someone else. I would love to sing to the baby.”

“You can sing—”

“I said to the baby, not you, okay?”

“Okay, fine,” I said. And I don’t know where I got the courage, but one hand left her foot and traced her tiny blue mole on her thigh. I brushed my fingers as if it could be erased. It was tiny and blue. Then, both my hands went back to her feet again. Taína’s gown had finally risen all the way up past her full stomach. Her bra was decorated with pictures of the Tasmanian devil from Looney Tunes.

Taína must have felt the draft and quickly opened her eyes and pulled her gown down and straightened up a little, though she still lay on the couch like she was sunbathing, her feet at my lap. Taína licked her lips and stirred. She must have known I was looking, but she didn’t seem to mind and didn’t tell me anything.

“My thighs hurt, Julio.” Eyes shut. “Rub my thighs.”

And my heart jumped.

I slid my hands up Taína’s thighs, gently, and I knew I would not be able to help myself as I felt wet and hot, and then I heard a voice coming from Taína’s room.

“Peta Ponce, Peta Ponce, ayuda a mi nena,” Doña Flores moaned.

Taína sprung quickly and, as best she could with her heavy body, lifted her legs away from me back to a sitting position. I straightened up, too, and placed my hands in front of me. Coming from Taína’s bedroom, we heard Doña Flores talk in her sleep. “Peta Ponce, por favor, dime, dime que pasó, Peta Ponce.” And then she crashed again.

We stayed silent for a minute.

All we could hear was the TV on low volume.

“My mother can’t know you were here while she was asleep.” And she walked me to the door, but before ushering me out, Taína got on tippy toes and kissed my lips. It was a nice, slow kiss with no tongue, but a kiss. She then closed the door.

And I was left standing in a silent hallway. But that was okay. It was all okay, and it reminded me of my father sending that note to my mom: When I saw you flowers started growing in my mind.

* * *

—

MY MOTHER CAME along and she spoke for a long time. The doctor listened to all her venting. Then the doctor told my mother that what I was going through was nothing new. Many boys fall in love with pregnant women, he said. The marvelous gift to bring forth life. He said there were men who only liked looking at pregnant women. Men who got excited by it. The doctor went on and on, and my mother slapped my shoulder and interrupted him.

“Tell the doctor,” she said, cutting him off, “tell him about your atom thing, tell him.”

I repeated my theory of the subatomic pregnancy with a few new twists and turns. How in the darkness of inner space anything was possible.

“You do know that the atoms you were born with are all gone,” the doctor said. “You are now made entirely out of new atoms?”

I knew this and nodded.

“Then how can an atom start a revolution when we lose atoms all the time?”

“Yes, it takes time, doesn’t happen overnight, about a year, maybe?” I said. “So this leaves the rebel atoms enough time to plant copies of themselves in the new cells that they created. Sort of like when a martyr is killed, but the revolution lives on and becomes even stronger.”

“You do know”—the doctor frowned—“that this is highly unlikely.”

“Yes but then,” I said, “if we are made of atoms and all our original atoms are replaced by new atoms”—the doctor crossed his arms—“how can we still be us when all that we were, all our original matter has been replaced?” And he frowned as if he had never thought of that or as if he were bored.

The doctor sat back on his chair. He looked at Mom.

“Is he under any medication? Anything?” He was trying to show an interest in me, but I could tell he was now putting on a show for Mom.

“No,” Mom said.

The doctor swiveled in his chair to face me again. He looked in my eyes and then faced my mother again. He told her it was nothing to worry about. That this wasn’t psychotic behavior. I didn’t speak of hurting myself or anyone else, and that I was just holding on to a crush or something and that he was a doctor and not a quantum physicist. It was something quite beautiful, he said. How the young can be so innocent in a very adult way. It was such a shame how as we grow up, we lose this. That is why, he continued, it is during this stage in puberty when the friends we make are the ones that we try to mold ourselves after. It was only when Mom sighed loudly that he stopped his lecturing.

The doctor asked me if I wanted my mother to leave the room. I said no and so he asked me point-blank.

“Have you tried drugs?”

“No,” I said, which was true.

“Have you smoked pot?”

“Yes, once.” I had forgotten that that was a drug, though I had never seen anyone die from a pot overdose. The other day BD had found a dime bag inside a Coke can by the gutter. It might have belonged to a dealer who was arrested on the street and didn’t have time to get his pot back. So we smoked it. But it was only once, and we might have not even smoked it right because I didn’t feel anything and just coughed a lot.

“Ay Jehovah,” my mother whispered to herself. The doctor ignored her because he must have felt he was on to something.

“Then you have done drugs?”

“I guess.” I shrugged, not wanting to face my mother, who was already thinking of what to say to my father, and more important to her elders, at the Kingdom Hall.

“Do you take alcohol? Do you drink?”

“No, but—”

“So you have tried alcohol?”

“No,” I said.

Eventually the doctor stopped asking questions and silently reviewed my responses, which he had written down. Then he opened a drawer and brought out a Dixie Cup with the Simpsons cartoon on it. He didn’t have to tell me anything. But he did.

“I need a sample.”

I snatched the cup and breathed out hard like Taína does when she is bored or sick and tired of things.

Outside the doctor’s office, Lincoln Hospital’s psych ward was painted a soft pink like a day care center. Its tenth-floor visiting lounge had a huge window where patients got a great view of the New York skyline. Many patients found it beautiful. Many had pulled their chairs to face the large window. Or maybe the skyline reminded them of their lost freedom.

In the men’s room I filled the cup and brought it back. The doctor repeated to Mom that it was nothing to worry about and that my urine sample would tell him the truth if I was doing drugs or not and, if I was doing drugs, what kinds of drugs I was taking. Depending on what the drug was, this might be the cause of my hallucinations. That’s what he called them, hallucinations. And that if she was so worried, she could always make an appointment for me to see a specialist. And with that my mother was happy. Me? I was glad it was over and felt like I had gotten off easy.

Verse 9

I WAS ON my way to take some pictures for Sal when I spotted BD sitting on a housing project bench not far from the mailbox. The left sleeve of the Izod shirt I had bought him was dead limp. BD was crying, an angry, bitter cry. He was cursing to himself. He had been waiting for me.

“That motherfucker took it.” He dry spat, his eyes had more water than his mouth. “Took my iPhone, too.”

BD had been going around school wearing new clothes, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch, and everyone had seen him at the latest movies, at Chipotle, Shake Shack, and showing off his leather jacket while counting his hundreds, living larger than a rapper.

“He wants a cut, Julio.” Mario had beaten BD up because he would not tell him what our scam was.

“Okay, don’t worry. First thing we got to get your arm back.” Because I didn’t know how much those things cost, but they must cost a lot and his mother would kill BD if he didn’t come home with his arm.

“How?” BD wiped the tears from his face and spat some phlegm and cleared his throat. “He wants five hundred for the arm.”

“Let’s just get your arm back,” I said.

Mario lived on Pleasant Avenue in a nice tenement near a church. And while gentrification had tamed El Barrio, it could not rewrite its past. Pleasant Avenue is a six-block stretch that runs from 114th Street to 120th Street, just east of First Avenue. It’s an Italian enclave shown in the movie The Godfather. The scene where Sonny Corleone beats up Carlo and leaves him bloodied by an opened fire hydrant. Italians and Puerto Ricans have been going at it since.

Things are much quieter now, but every once in a while someone like Mario De Puma shows up and bad blood starts up all over again, because like aluminum cans, the past is recyclable.

We reached Mario’s door and knocked.

Mario’s father opened. He was smoking a cigar and bopped his head as if to say, What you fellas want? He was a bigger, stronger version of Mario, with hands like milk crates. He could suffocate you with three fingers. Hairy knuckles stuck out like bedrock in Central Park.

“Mr. De Puma,” I said nervously, “my friend is missing an arm and your son took it.”

Mario’s father looked at BD’s limp sleeve.

He removed his cigar and laughed like Santa Claus.

“We just want the arm back, that’s all.” Making nothing of his laughing. But he couldn’t stop.

“So let me get this straight,” he said with no real Italian Hollywood movie accent, just a nasty brute voice, “your friend here got into a fight with Mario and couldn’t protect himself?” He kept laughing. “And Mario took his fake shit arm?”

BD didn’t say anything. I didn’t say anything either.

“Now, whose fault is that?” he said, putting the cigar back in his mouth. Through the opened door I saw a fat lady ironing clothes in the living room. On the walls were pictures of her children. There was Mario as a little boy in a sailor outfit chasing ducks in Central Park. He looked nothing like the bully he was to become. There was also a cross and a picture of Brando, Sinatra, and DiMaggio, as well as snapshots of the pope.

The fat lady stopped ironing for a second and said, “Arm? What arm? Whose arm? Arm what?” She continued to iron. Mario’s father turned toward her and told her what had happened.

The heavy lady didn’t laugh. She kept ironing and then shrugged. “So, give him back the arm.”

“No, no, wait, I asked these fellas a question,” Mario’s father said, turning back to us. “Because Mario is a man. I’m proud of my boy. A real man, that Mario.” He looked at BD and me. “Actually we are all men here, right?” And only I nodded because BD had started to fade. His humiliation was growing. “Not pussies, right?” he said. “What’s in it for me?” He put his cigar back in his mouth and crossed his arms.

“What you mean?” I said.

“If I give you back the arm, what?” He smoked away. Waiting for us to say something.

He took out his cigar, spat, and put it back in his mouth, holding it down with his side teeth.

“You know who my father was?” I didn’t. BD was about to cry. “They called him Vinnie the Butcher. He owned the butcher shop on 119th Street and First. You know he never sold a single pork chop? The red stains on his apron never changed, they always stayed the same, because that shop was just his thing, you know, his thing, to make money.” And he blew a lot of smoke in the air. “But you people arrived and ruined what was a once a great neighborhood. No one had to lock their doors on Pleasant Avenue before you people came.” He crossed his arms and bobbed his head

. “My father didn’t have to sell a single pork chop because that shop was just his thing, but when you people came, your dumb mothers would walk in and ask for meat. Ask, why was there no meat? Ask, this is supposed to be a butcher shop and there was no meat? Your mothers made a big deal why was there no meat? You ruined his thing. You people ruin things and now you want your arm back!”

“That’s not our fault, sir,” I said respectfully, but he just got mad.

“What’s not your fault, pussy?” He puffed away.

“What happened to your father.” And BD tapped my arm with his good one, telling me we should just go. “Those mothers didn’t know your father’s shop was a front, they didn’t understan—”

“What’s there to understand? I don’t like you people.” He barked, “That’s what’s there to understand. Now you want your arm back? My son took that arm from you and like the pussies that you people are, you don’t take it up with him but with me. You think that because I’m the father I’m going to be all soft?” he yelled, and the lady ironing left her duty and stomped over.

“What color is your arm? What it looks like?” she said to BD, a bit annoyed at having to leave her chores.

“It’s an arm,” BD whispered.

“What color?” she asked again.

BD silently stuck out his hand and showed her his brown skin. She exhaled inconveniently like this was a waste of her time and left to check her son’s room.

Mario’s father was fuming at us by the door, blaming all Puerto Ricans for destroying his past.

“Before you people arrived, we could leave our fire escape windows open all night, no gates before you arrived. You people steal. If I threw a coin in a fountain, you people grab it before it hits the water.”

The lady returned with BD’s arm.

“Go,” she said, like shooing flies away with her hands. “Go, go. I have family to do.” And she returned to her ironing. Mario’s father spat some more tobacco and put the cigar back in his mouth before slamming the door.

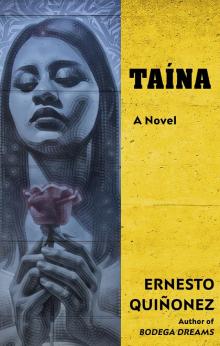

Taína

Taína