- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 13

Taína Read online

Page 13

Mario had written in big, bold, black letters FAGGOT on BD’s arm.

“You can cover it with your shirtsleeve,” I said to BD, who didn’t say anything. “No one will see it, BD—see? The sleeve will cover it. We can try paint remover, okay?”

* * *

—

AT SCHOOL I did my best not to run into Mario. As long as there were people around I was fine. I had a meeting with old Mr. Gordon, the guidance counselor, about applying to colleges and all those financial aid junkets. Other than Princeton, I didn’t really know which colleges to apply to since I really didn’t know what I wanted to study. So like people who buy wines according to how pretty the label is, I asked him about schools that sounded kinda cool. I said Pepperdine because it sounded like a character from Peanuts. Mr. Gordon laughed. He shook his head and said that I would never get in. Okay, what about Duke? Nope, he said, never get in. Vanderbilt, sound good? Nope, never get in. Bowdoin? Nope, never get in. Pomona? Nope, never get in. Swarthmore? Nope, never get in. Yale, sounds like jail? Absolutely not, he said, never, ever get in. Cornell? Nope. Dartmouth, funny name? Nope. Princeton? Never in a million years get in. When I said Harvard, he stopped me and gave me a long list. Told me to google these schools’ admissions pages and that I should be fine.

A little later I was walking in the hallway, avoiding Mario at all costs, reading the list of colleges, when Ms. Cahill saw me and asked what I was reading so intensely.

“That’s it?” She frowned. “Only community colleges?”

“He said that even if I make it into the private schools, I would be in debt all my life.” Sounded wrong to me, but I had been taught to respect my elders in public and trash them behind their backs, so I’d stayed quiet when he told me this.

Ms. Cahill blew an angry loose strand of hair away and led me to her empty classroom. She closed the door and asked me to sit by her desk.

“Where would you like to apply?” she asked.

“Princeton”—because I knew Einstein taught there—“though I don’t know if I want to study science. I like it, but I don’t know. I could also live at home and cut costs.”

“That’s a great idea and great choice,” she said, and then lowered her voice, though it was just us in that classroom. “There are some teachers”—she said this carefully, but I knew whom she was referring to—“who come from a different era. Who have been teaching here since the 1900s and think like we are still living in the 1900s, too. Now, I read your college essay, Julio.” And she fondled through a mess of paper on top of her desk and found it. “It was excellent. It’s what colleges look for, Julio. People who help others. And you wrote it in a creative, concise, and precise, grammatically correct structure. Did you really befriend this ex-convict, really?”

“Yeah,” I said. “But the essay is not finished.”

“Good,” she said. “Please finish it and show it to me before you send all your stuff out. Listen, Julio, your grades and your AP scores are also good. Not excellent, but good—” Her iPhone on the desk vibrated. The screen showed a picture of a cop, only his shirt was undone, exposing his bare chest. Ms. Cahill quickly answered it and said to call her later.

“Yeah, okay,” I said, “but I don’t want to get into debt, either.”

“Listen, I know scholarships are hard to come by. I myself did not get one. All I can tell you is…” And she thought for a second how to word this. I think she was trying to find something specific within my life so as to use that as her base. “You go to church, am I right?”

“I used to,” I say, “but yeah, sure.”

“Okay, listen, I think you heard the saying, I think it’s in the Good Book, that says if you don’t work, you don’t eat. Am I right?”

“It’s Paul,” I said. “My father, who’s a communist, told me that Lenin used it, too. Weird, huh, Ms. Cahill?”

“No, not at all. Christianity and communism aren’t all that different.” And just when she was going to continue, her iPhone rang again. On the screen was a picture of different cop, only this one had no shirt or anything. He was completely nude, letting the taco fly with only his cop hat on. Ms. Cahill tried to turn it off before I could see it, but I played it off. “What I need to tell you is, listen, there are people who are born with bread and never have to work. There are people who inherit bread, their uncle dies and leaves them money or parents die and leave them money. There are people who win bread, they hit the lottery or some sweepstakes. The saddest and most unfair part of that phrase, Julio, is that there are people who work very hard under the sun like migrant workers do picking strawberries or lettuce and they receive very little or no bread.”

“I get your point,” I said, but I wanted to ask her about Taína, about the day she sang. I knew she had been present. But I let her finish.

“Great, Julio, because what no one can inherit, win, find, or work for, is…more…time. Time is the real gold. Not money. Time is the gold. It’s what you do with your time that matters. So if you want to apply to Princeton, I will help you. You have a shot. Debt or no debt, you would have used your time well in reaching for what you want, and it’s a great thing.”

She held my eyes for a second. I didn’t tell her that I knew old Mr. Gordon was full of shit.

“Ms. Cahill,” I said, “can I ask you something that has nothing to do with this?”

“Ah, ah, ah, sure,” she said nervously, because she knew all the boys liked her. I think she knew she was gorgeous, and this can be a frightening thing, I think. Taína didn’t know she was gorgeous.

“You remember Taína?”

“Taína?…Taína? Oh, that girl. Such a sad thing.” Her tone changed, like she was talking about a hurt puppy. “So, so sad.”

“She once sang in the music room. You were there, right?”

“Was I?”

“I’ve heard you said that everyone saw whom they loved and who loved them back. Is this true?”

She focused her eyes somewhere else and thought about this for a second. Her eyebrows wrinkled and then she opened her mouth a bit and said, “Ah, yes, I do remember her singing. Lovely, lovely voice. Truly lovely.”

“Well, is it true that you saw people you love?”

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah, I heard that you said that.”

“Well, maybe I did at that time, but what I recall…” Pausing, scanning her memory. “What stands out was how Mario, you know Mario? Everyone knows Mario. How he was so taken by her singing he sort of shriveled up in his chair.”

“Mario?!!!”

“It was a bit funny how this tough guy was moved by her singing and just melted.” She laughed a little laugh.

“Mario?!!!”

“Yes, Mario. Before she stopped attending, I thought they were a couple because when I’d see them, they were not far from each other. That’s you kids and love. I throw no stones, I love, love.” She smiled. “I love, love. Love it.”

“Mario?”

“Yes.”

“No fucking way!!!”

Verse 10

I WENT TO take some pictures. I arrived at the Capeman’s playground. It was drenched in sunlight and color. There was a big blue sign graffitied on the handball court: IF YOU GENTRIFY, THEY WILL COME. In Salvador’s days, this part of the city was called Hell’s Kitchen. It was full of greasy diners, prostitutes, pimps, hustlers, and junkies, as well as hardworking people and their families who went about their business living in affordable apartments. The playground had been remodeled, surrounded by a new and shiny white wired fence. There were fresh wooden benches lining both sides of the playground. Right in the middle, like an island, was a little, vibrantly painted storehouse where the custodians kept their brooms and cleaning stuff. There was a fresh sandbox and a long silver slide next to a row of metal swings. It was here, on the swings, where the two boys an

d their friends were just innocently shooting the breeze before the Capeman and his Vampires arrived. I walked a little farther up and took pictures of the Sixteenth Precinct on West 47th where the Capeman had been booked. I had bought Sal a camera as a gift and was shooting pictures in the daytime so he could see these places in sunlight. I planned on giving him the camera and the pictures so that maybe he might want to go out in the daytime and shoot pictures one day.

Back home, I turned on my laptop and googled the bejesus out of Sal. Everything I could find. All his life as the Capeman and a bit after. I sat on my bed and read, doing research and taking notes for my college essay:

Salvador Negron was 16 when he was tried as an adult in the last year of the doo-wop 1950s. He was the youngest ever to be sentenced to death by electric chair. For two years death slept, ate, and breathed with him, and laughed at him, until that fateful day. For his last meal, he had ordered Puerto Rican dishes: pernil, arroz con gandulez, flan, and a tall glass of maví. But all he got was fried chicken, mashed potatoes, green peas, garlic bread, and apple pie. He ate his last meal sadly, but he was happy that he might see heaven in a couple of hours. Afterward, when his name and number were called, “On the gate!” he fainted. When he opened his eyes, he was not in heaven, or strapped to a chair, but rather back in his cell courtesy of a last-second pardon by Nelson Rockefeller, who was governor of New York.

I stopped reading. All I could think of was that first day I met him. How he reminded me of an old broken-down Jesus Christ, whose disciples had long ago deserted him.

Verse 11

TAÍNA OPENED THE door. She held a finger to her lips. “Mami is asleep in my room again,” she whispered. “Don’t make a sound, dummy.” And I angrily tiptoed inside. I could see that Doña Flores talked in her sleep as she snored a ghost story. We sat on the couch. I felt Taína’s warmth as hot as my anger. Taína was wearing the same see-through gown, though this time she had not thrown a T-shirt over it—and those colors arrived. I saw red circles doing circles inside blue circles inside white circles and my heart was pounding to those circles.

“It’s sausage, mushrooms, and peppers, you better like them,” I said, trying not to look. “I wasn’t sure what you wanted so I just picked these. If you don’t like them it’s too bad.” But I gave myself away and Taína knew I was looking at her breasts and crossed her arms. “And oh, I got you gum.” I folded. I tried to be nice, even though I was still angry.

Taína, who had made a big stink about wanting gum, didn’t take the gum. Instead she went for the pizza. She sat on the couch.

“This pizza sucks,” she said, continuing to eat, “horrible pizza.” And soon she picked up another slice. “Terrible, where you get this shit pizza? I should starve before I eat this crap.” But she kept eating.

I pretended to watch television, a Pixar movie at low volume. I wanted to kiss her like before. Pick up where we had left off. But Mario hung in the room.

“Next time bring some Coke. Who brings pizza with nothing to drink?” She ordered me to get her something to drink from the kitchen. She said that really loudly, even though when I first walked in she had told me to be quiet. “And I don’t want orange juice,” she yelled from the living room. And Doña Flores slept like a rock.

But there was nothing to drink in her almost empty fridge but orange juice and milk.

When I brought her a glass of milk, she made a face.

“Are you fucking retarded?”

“That’s all you have,” I said, “and you said you don’t want orange juice.”

“So get me water, then, jeez. Can you do that? Can you?”

So I got her water.

“ ’Bout time,” she said, and took a sip.

I was hungry, but I didn’t eat anything and let her have as many slices as she wanted. I enjoyed watching her eat. I liked the way her lips shone from the pizza’s grease and how her temples went up and down as she chewed. I could understand why any guy would fall for her.

When my mother had to say something to me that she didn’t want to talk about, she would just say it. She would come out and set it free without thinking, like jumping into cold water. Straight up.

“Mario.” If I stayed calm and didn’t get myself pissed off and concentrated, I wouldn’t yell, I thought.

“Mario who? Mario what?” She shrugged.

“Mario, from school. I’m sure you know him.”

“Who again?”

“Mario, Italian guy. Big with muscles and nothing up there.”

“Oh, that guy?” she said.

“Yeah,” I said, “that guy.”

“He was nice.”

“What?”

“No, he was one of the few who never said anything mean to me. He would leave me cannoli on my desk, I’m serious.”

She must have seen my angry nostrils or heard my heart beating like a conga. She smiled and lifted her head as if she now knew what this was all about. Why I was mad at her.

“Ya sé qué bicho te picó.” She shook her head. “You men all the same.”

“I’m leaving,” I said.

“That’ll be your fucking loss,” she said loudly. “Because nothing happened.”

I didn’t leave, but I couldn’t look at her either. I gave her my back. Her bedroom door in front of me was wide-open. Doña Flores was stiff. If she weren’t making noises or talking in her sleep, you’d think she was dead. Her body lay facing the ceiling. Her hands lay folded on top of her chest and she was wearing a nice blue dress, as if she had just come back from a party or as if this was her funeral bed.

Taína turned me around. We came face-to-face. She saw my unhappiness. For once Taína looked more nervous than me. For a second she played with a strand of hair before tugging it behind her lovely left ear. She licked her lips and gently pushed me to sit on the couch. She then gently sat her pregnant body next to me.

“You know that your mother left my mother flat?”

“Yeah, I know.”

“Just when my mom needed her support.”

“Yeah, I know.”

“I won’t call your mother a bitch only cuz I know you. So you know, with her best friend gone and shit, my mother met this guy. My good-for-nothing father, who was one of those Latinos who fucking hates other Latinos.” Her tone was soft, but the color was still there.

“I heard,” I said. “Your uncle Sal told me. What does this have to do with Mario?”

Taína paused. Her angry eyes told me not to interrupt her again.

“If you fucking let me talk, bitch…I will tell you. God….Mami was pregnant with me and all she’d hear from him was how Latinos hate each other. He blamed all Latinos for him growing up in the South Bronx, for his father’s shit job at a factory, for his mother’s shit Social Security checks, he blamed Latinos for where he lived with Mami, for this shit housing project, for any shit he’d blame Latinos. Especially Puerto Ricans, which he was but he hated them more than anyone. He said that we had been in this shit country before the other Latinos arrived and we hadn’t done shit. That Mexicans had taken over California and that Cubans owned Miami, and that even those fucking Koreans had cornered the vegetable market stands, but Puerto Ricans had done shit. He used to work at a bank in midtown, Mami told me, that’s where they met. She had to cash her receptionist checks there. He was a good teller, from what Mami tells me he was great with numbers. I hate fucking numbers, so I’m happy I inherited shit from him. But he loved working with white people at that bank. He was going to night school in trying to better himself, too, Mami said, but one day when a promotion was due to him, they passed him over and gave it to a black guy.” She paused and saw how mad I was. “Jeez, it’s hard to tell you this when you look like I killed your fucking dog—”

“What does this have to do with Mario?” I did my best to breathe silently.

“I swear to God if you say that again before letting me finish, I will bitch-slap your fucking face so har—”

“Fine, finish.”

“My good-for-nothing father was okay with this black guy getting the promotion. Until he found out that that bank manager who spoke great English and had gone to college was not a fucking white guy but Dominican. A fucking white-skin Dominican in charge of everyone in that bank. All of a sudden it was how that fucking white Dominican had kept him down. Latinos, he would say, we hold each other down in water so we can drown. He was fired and never came home. That fuck left Mami with me still inside. This is what Mami tells me. I never saw him, never met the fuck. I hope he’s dead. I hope he fuckin—”

“Mario,” I said, “did—”

“Hold your horses, I’m trying to explain this shit. So when I was like eleven and knew that guys were looking at my ass, you know, when I knew this I steered away from Latinos. So when at school an Italian guy liked me, you know, brought me cannoli, I thought, Okay, he’s not Latino. This is okay, you know, this is good? And you”—she poked at my arm—“you were cute but Latino and never said shit to me, you were like chickenshit scared or a big wuss.”

“You think I’m cute?”

Taína just smiled and exhaled. I did not mention to her that Italians were Latins because I kind of understood where she was coming from. Her father was ugly, and he had been raised during a time in the South Bronx when vacant lots grew like toxic gardens. He’d grown up surrounded by street boys that if caught stealing they’d lie, if beaten they’d curse, if sent to prison they’d go kicking and screaming, blaming the world for hating them. I could only think that Taína’s father had tried hard to avoid being like them. Though he had not ended up dead or in prison, they had already infected him. He was a carrier of the ghetto. So why would I blame Taína? She was defending herself as best she could from the same brutality I was trying to dodge. Didn’t mean I had to like it, though.

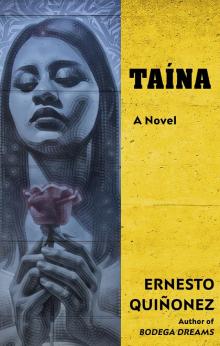

Taína

Taína