- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 3

Taína Read online

Page 3

“M-m-my, real name is Sal-Salvador,” he stuttered a bit. “My mother when she was alive”—and he crossed himself—“would call me Sal. But once when I was about your age, I was famous.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. I was all over the papers, papo. Time magazine, Newsweek. When I was your age,” he said in the saddest of sad tones, “I was the Capeman.”

Verse 1

MY FRIENDS AND I were sitting at our corner of the lunchroom. They served pizza and ice cream. I was holding court.

“Can’t you guys see, like something happened inside, really, really, inside her body and it produced sperm cells instead of blood cells or skin cells or bone cells, or anything like that.”

“No way,” BD said.

“Why not? It supposedly already happened once, right?” I said.

“Yeah, but that was God.” BD had lost an arm because of his need for trouble. His mother would actually want him to sleep in, to wake up late in the afternoon, because then he’d have less time to get into trouble.

“God had nothing to do with it,” I said.

BD had lost his arm on a dare. Some kid challenged him to jump down the subway tracks of the 103rd Street stop and walk across from one platform to the other. BD survived when the train came out of nowhere, but he did lose an arm. Because of his prosthetic limb, everyone in Spanish Harlem stopped calling him Hector and called him Bionic Dude. In his pocket, BD always carried a picture of himself when he had both arms to show everyone that he wasn’t born that way.

“Things can happen only once,” Sylvester said. “I lost my virginity. See, only once.”

And we snapped, “You wish!”

Sylvester’s real name was Elvis, but when he talked, he gave you the weather. The guy spat all over the place. No one called him Elvis. Instead everyone called him Sylvester like the spitting cat in cartoons. He was not really my friend because he was the worst person to eat with, but he was not a bad guy. And he never returned the pencils he’d borrowed, and if he did, they had teeth marks on them.

“Listen, all I’m saying is our moms drag us to church every Sunday to hear about something like this happening. And it’s happening again, today.”

“You crazy,” BD said.

“Everyone knows she was attacked,” Sylvester spat. We covered our trays.

“She was not,” I said, and wiped my arm where some spit had landed. “Her mother said she was not. Her mother keeps an eye on her like twenty-four/seven. So she should know. And I know for sure because I went to see that dude who attacked those girls.”

“That’s bullshit.” BD was about to dig in his pocket for Jolly Ranchers.

“That’s right, and I talked with him in prison and he said he didn’t do it.”

“Yeah, but that’s what all convicts say, man,” he said with a mouthful of meat loaf. “Everyone says they didn’t do it.” Sylvester spat chunks.

“Didn’t I just say I talked with that guy—”

“How you get there?” BD asked.

“My father drove me, and I went inside that prison. It was just like on TV, a lot of skinheads, Aryan Nations, Bloods, tattoo guys lifting weights and stuff. Just like in Cops.” I was happy when they believed me.

“Hey, okay, fine,” Sylvester said, “but he ain’t the only rapo around. Maybe it was some other guy who did it.”

“No way,” I said.

“Yo, listen,” BD said, “her toto was invaded, that’s it, all right.”

“I don’t know why you Dominicans call it toto,” Sylvester spat at BD. “Shouldn’t it be tota?”

“Fuck you, why don’t you go give the weather somewhere else?” BD said.

“No, why do you Dominicans call it toto?” Sylvester drank some milk. “That’s like male. See, in PR we called it chocha, see, that’s female.” And milk rained.

“Can you guys shut the fuck up,” I said.

With his good arm BD brought out Jolly Ranchers from his pocket. “Want some?”

We took one.

“You know Taína can sing, right? Right?” I said.

“I was there,” BD said. “I heard her.”

“You were there?” I was excited to hear this. “You never told me, BD.”

“Me and Sylvester were both there. Man, there was no more room at typing. So they had to accept us at chorus. Whack.” BD laughed. “When the class saw Sylvester walk in they all moved to the opposite side of the room.”

“That’s bullshit!” Sylvester rained spit defending himself. “I can carry a note, motherfuckah.”

“Yeah, but you a fire hydrant, bro,” BD said. “And everyone knew it. But Taína was the only one who didn’t move. She just sat there and waited for her part.”

“What happened?” My best friend had actually been there. I wanted to hear all about it. “What happened? What happened?”

“Nothing.” BD shrugged. “She sang. It was good. That’s all. That’s the last I ever heard her talk or anything.”

“That’s it?” I said. “But Ms. Cahill said all these things about her singing.”

“Nah,” BD said, “it was just singing.”

“See, that’s why you don’t know shit ’bout music, BD,” Sylvester said. “Yeah, all right, I might spit a little bit, but—”

“A little bit? Nigga, you got tsunamis coming out of your mouth.”

“Let ’im talk, BD,” I said, because Sylvester had been there, too. “Let ’im talk.”

“Thank you, Julio,” Sylvester said. “Cuz BD don’t know shit about music, but I know music. I know cuz when that girl got up to sing it was like a radio had been turned on. Ms. Cahill and everyone outside in the hallway came into the music room to hear. They had a face like ‘Holy shit, this ugly duckling is a swan.’ ”

“Taína is not ugly,” I said, “but what else?”

“She hit like six or seven octaves.” Sylvester then looked at BD. “You know what an octave is?”

“Yeah, it’s when your mother fucks an octopus.”

“What else, Sylvester, what else?” I said.

“It was beautiful, man. Then she clammed up, never heard another word from her.”

“Didn’t sing again?”

“Didn’t speak again,” Sylvester said.

Just then we all tensed up. Mario was coming our way.

Mario De Puma, the Italian kid we had grown up with. He was now twenty years old, a super-duper super-senior. He had a year left before he’d turn twenty-one and the public school system could legally kick him out. Mario was like the Incredible Hulk from the comic books that he was always reading. He was stocky, but all muscles. His hands looked like they could tear the phone book in two. He lived by Pleasant Avenue, next to Rao’s restaurant, the last stronghold of the old Little Italy section in Spanish Harlem. Everyone knew his father because he was just like Mario, not very bright but a boulder of a man. Some said Mario’s father had been an enforcer for John Gotti.

During lunchtime Mario would play out this scene. He’d pace around the table where my friends and I were still eating. His hand held an opened pint of milk. We knew he was going to pour milk on one of us.

That day when we spotted Mario coming, we all stopped talking, held on to the Jolly Ranchers in our mouths, and stared ahead, hoping to not be the one Mario chose to pick on. But I felt his presence behind me. He hated me, called me psycho. Then I felt the cold milk being poured down my neck, running down my back and into my jeans.

I heard Mario laugh.

“Don’t get mad. You’re a wetback anyway,” he said. “Don’t get up. Mexican, Puerto Rican, Dominican, all wetbacks.”

But I shot up and seriously looked straight at him.

“Oh, shit, it’s you, psycho.” He didn’t know. “What you gonna do? I’ll hit you so hard your children will b

e born dizzy.”

I wanted to hit Mario, though I knew he’d kill me.

I slowly sat back down.

“I’ll tell you something about that Taína, psycho,” he said really loud so the whole lunchroom could hear, “I did that dumb box. I’m the father.” And then Mario laughed, walking away really proud of himself as if he had just slaughtered some big game.

“I got a sweater in my backpack you can borrow,” BD said, “or you can use it as a towel.”

But I was furious and felt like crying. The milk was running down my back, becoming colder as it wet my underwear.

* * *

—

I WANTED TO be part of Taína’s life. I wanted to be able to somehow make Taína’s breaths coincide with my heartbeats, the way I had read some Buddhist monks did with the universe. So that even when the monks were sleeping, their heartbeats were in tune with all things. I wanted to feel like that. To always have Taína beating inside me. To one day hear her sing and see love, really see love, coming through her lungs. But Taína had shut herself off from the world, and el Vejigante knew.

I needed to know more about him. So, after school I visited the Aguilar public library on 110th Street and Lexington. I knew what a vejigante was and why they called him that. The old man was tall and skinny, like he walked on stilts. But I didn’t know who the Capeman was. I sat at a computer and googled that name.

The pictures that came on-screen were of a skinny kid not much different from me only way taller, with hazel eyes, and in handcuffs. His full name was Salvador Negron, born in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. He was shuffled from New York City and back to the island by his parents as many times as he would later be shuffled from juvenile detention center to juvenile detention center. From prisons to asylums to prisons once again.

Wikipedia said that it was the last year of the fifties. The New York City streets belonged to doo-wop groups and teenage gangs. Some, like the Vampires, were both. They choose a subway platform, throw a hat on the cement, snap their fingers, and soon a cappella grooves would be bouncing off the subway walls. They added melody and harmony to the underground, and many gangs made a few dollars this way. It was common knowledge, a known rule among the doo-wop gangs, that the subway was for all, but above ground, the singing street corners were turf wars. As the lead singer of the Vampires, Salvador liked to choose singing corners that other doo-wop gangs considered theirs.

It was late in evening when the playground killings occurred. All over the Upper West Side from the 100s down to the 70s, the large population of Puerto Ricans that lived there before gentrification, before the cleaning of Needle Park, was taking in the street nightlife of radios blasting salsa. Of opened fire hydrants. Everyone looking for someone to dance with, looking for someone to love and to be loved in return. Everyone cooling off from a summer heat wave. It was later in the evening when word arrived to Salvador that some kids from a doo-wop white gang, the Norsemen, had beaten up a Puerto Rican member. As lead singer and president of the Vampires, Salvador rounded up his boys. He instructed the Vampires to meet on the Norsemen’s turf, a playground on 46th Street and Ninth Avenue where the Vampires would sometimes sing without any permission.

Some Vampires came walking, some took the bus. Salvador jumped the turnstiles and took the 1 train, got off at 42nd Street, and then headed west. He was wearing his cape and he carried a dagger along with all that hate, anger, betrayal, and abuse—a wealth of tragedies just waiting for an excuse to be set free. It was a moonless midnight in a New York City neighborhood known back then as Hell’s Kitchen. The playground was dark. The lampposts were broken. Doing nothing but hanging out by the swings were a couple of white boys.

“Hey, no Norsemen in this playground,” Salvador yelled at them, feeling all right. He was with his boys, with his troops. Like when he sang lead, his Vampires were backing him up. The white boys ran. Salvador and his Vampires chased and fell on two of them. Salvador kicked one of them down and started screaming at his face, “This is our playground. No Norsemen! No white Norsemen!” His dagger stabbed the white boy. And then Salvador stabbed the other boy, too…but these boys were not the Norsemen. They were not gang members. They were just innocent white teenage boys hanging out at this playground at night.

Bleeding a crimson river, the first teen made it to the entrance of a tenement building. He knocked on a first-floor apartment, and an old Irish lady quickly recognized him as one of the boys from the neighborhood. The old lady knelt down. Held the bloodied body in her arms as if she wanted to give him what was left of her life. He in turn closed his eyes, made garbled noises like a baby learning to talk, and died in her old arms.

The second bleeding teen made it to his apartment building across the playground. He managed to drag himself up a flight of stairs and knock at his apartment door. His mother opened it and found her bloodied son gasping for breath like a coughing radiator. She held him, crying, as he died in the hallway.

This was what Wikipedia said, and many of the pictures on the computer screen showed a handcuffed, tall, skinny kid at the police precinct wearing a cape just like the one el Vejigante wore. His eyes were angry and red, as if he had been crying a dry, angry cry that burns your throat.

This happened a long time ago in my city, though I could not recognize it, yet it was the same city, and the kid on the screen looked nothing like el Vejigante did today. He was just a kid whom the media called the Capeman.

I logged off.

I was not scared by what el Vejigante had done when he was my age. I was still determined to meet him later that night because I would do anything to be part of Taína’s life. Hear her sing. But one thing had scared me. It was what Salvador was quoted as saying that night, long ago, when public rage demanded blood, the Capeman’s blood, and called for execution by electric chair.

“I don’t care if I burn,” the Capeman said. “My mother can watch.”

Verse 2

THE THINGS THE Capeman had said about his mother had stayed with me. Mom had warned me not to visit Taína. I wondered what she would do if she knew about el Vejigante’s past. And me talking to him. And meeting him later that night. Mom would always say, “Pa’ Lincoln Hospital is where I’m taking you. Pa’ Lincoln, otra vez, pa’ Lincoln.” And I’d get a bit scared because I had been to that hospital a few times and never liked it. Mom had taken me to the psych ward when I was thirteen after I said that Jesus was stupid for curing the blind. What he should have done was cure blindness. Jesus was also dumb for bringing Lazarus back from the dead. Why not just get rid of death? Made sense to me. But Mom said that what Jesus did was show a taste of what the Kingdom of God will bring. I said, Why wait? Just bring it. Mom got mad, and so off to Lincoln Hospital we went. She missed a day’s work, too, and told the doctor that I heard voices and acted as if I were crazy.

Yes, I do see things. I do. I do have visions; some people call them daydreams, but mine are vivid and they help me. The things I see are there to help me and no one else. I don’t force them on anybody. I told this to the doctor, and he nodded and then scheduled more appointments.

I remember a skinny girl during one of my visits. She had tried to kill herself by drinking Drano. She was interned at the ward. Received some money from somewhere, but no one visited her. She couldn’t go outside or down to the cafeteria to buy candy bars. She’d always ask visitors if they could go to the cafeteria on the ground floor and get her Snickers. She even had the money in hand. All she needed was for someone to go and get the chocolates because the doctors wouldn’t let her out. During one of my doctor visits, I brought Snickers bars with me and a nurse saw them. She said not to give them to the skinny girl. I listened to the nurse. Twice a month Mom would take me for my sessions with the shrink and I’d see the skinny girl. At first I thought that they were doing the skinny girl a favor because of weight issues, but that wasn’t it. “She will say they are stale. Thro

w them at your face,” the nurse told me, “and then yell curses and it will be us who will have to put up with her. Not you. Us. So don’t buy her any chocolates, please.” But I’d still bring Snickers, and one day I decided to give them to the skinny girl. She thanked me. She even paid me and went to a corner of the visiting lounge to look out the window. She savored every bite, happy to be eating by the large window of the visitors’ lounge that is the pride of Lincoln Hospital’s psychiatric ward. The lounge’s window showcases all the projects of the South Bronx blending in with the wealthy New York City skyline looming at a distance. The skinny girl sat there as if she were watching a movie about two different cities living in one. Sometimes she would happily laugh to herself. The nurses and doctors were wrong. That’s when I wanted never to return to Lincoln Hospital. I began to lie to the doctor. I told him what he wanted to hear. That I did not see any more visions. That his sessions were working. His pills, too, though I faked taking them. Soon, the doctor said I should return only if I heard voices or started to see things again. Great. No more visits, and just to be safe I told my mother that Christ was good, a pretty awesome dude. I mean, when the wine ran out, he turned water into wine so the party could go on, who could not love this guy? Hung out with whores and never beat, robbed, or jammed them. Great guy. He should be cloned. Yes, a true superstar. I even went with her to Kingdom Hall meetings, and that’s where I first noticed Taína.

* * *

—

I TRULY BELIEVED that a revolution had taken place in Taína’s body. No one had touched her. She was telling the truth. The fact that no one believed Taína made her pure and her story true.

One day while taking the number 6 train to school, I had a vision.

I saw Taína.

She was in her house.

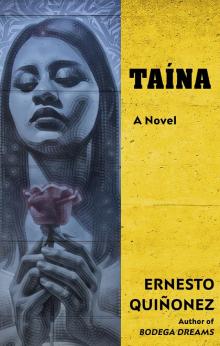

Taína

Taína