- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 4

Taína Read online

Page 4

It was early morning.

Taína woke up. Her body was feeling strange. She did not know what it was, but it was something. So she took an aspirin and made herself a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich and drank water. But soon Taína felt hyperaware—the beating of her heart, the fringe of her eyelashes, the expansion and deflation of her lungs—her body was talking to her. In my vision I saw Taína blink and stop chewing because the world suddenly appeared shimmery, blurred, and melting. All things around her seemed out of focus, as if something inside her had unexpectedly shifted. Taína took a deep breath full of fear and panic. Her heart pounded like it wanted to break her rib cage. Then, all of a sudden she felt light, this unbearable lightness of being, as if she needed more water because the weight of the liquid would keep her from levitating. Then, a deep clarity inside her inner universe whispered to her that it was okay to relax, it whispered that she was only pregnant. That a revolution had ignited inside her. An atom had decided to revolt in order to create life. This atom did not want to dwell in the infinity of Taína’s inner space and do as told. This atom did not want to shift its orbit or give up electrons when bonding with another atom in order to create the molecule it was supposed to. This atom felt the need, the desire, to use its electricity and its endless resource of nearby atoms to convince them that they are the building blocks of the cosmos and so they have the power to start again in a whole new body. Together, trillions of trillions of trillions of rebellious atoms drew up a blueprint. They would no longer do as it was written in the laws of Taína’s DNA or any law. They would now be the ones to decide what compound bonds to form, how many electrons and neutrons to include or exclude or share in their compositions, all with the ending goal of creating life. The revolution was in full bloom when millions and millions of newly self-created sperm cells went rushing after the egg that clung tenaciously to Taína’s inner heavens, and soon, a sperm got there and asked to be let inside. The egg said “yes.” The first second of year zero.

And then my vision was over.

I was back on the 6 train.

On my way to school.

It’s when I see visions like this one and others like it that I want to hold Taína, smell the shampoo in her hair, and whisper that she and the baby will be fine. That none of this is unreal. For Taína not to worry, because though rare, it is as natural as the fall of apples. Whisper to Taína that the revolution chose you. These rebellious atoms must have seen and felt something pure and kind in you, a body with no chains or kings or gods.

* * *

—

IT WAS TEN p.m. and my mother had finished watching her novela and was now listening to the radio as she was getting ready for bed. Sophy sang beautifully:

Locuras tengo por tu nombre / Locuras tengo por tu voz.

I was waiting for her to turn off the radio and go to bed. My mother worked at Mount Sinai’s basement doing the hospital’s laundry. She was always tired and went to bed early, and my dad was unemployed, so he was a bit depressed and slept a lot. I could easily sneak out of the house at will. El Vejigante had said to meet him at midnight by the mailbox that stood across the street from Taína’s window.

All of a sudden Sophy stopped singing, and a news flash about an earthquake in Aracataca, Colombia, came on the radio. Mom shot out of the bathroom, toothbrush in hand, and listened. The earthquake had triggered massive mudslides, tsunamis of dirt, water, and clay overrunning everything in their path. The voice said people were covered in mud as if God had just created them but had not yet breathed life into them. Rivers of clay were running away with huts and possessions. “Ay, Dios mío,” Mom said out loud. The voice continued, saying how people were trying to save their cows from drowning in clay pits. I could hear cows mooing furiously coming through clearly from the radio. The reporter said it was the worst earthquake in Colombia’s history, and my mother nodded her head like she knew this was Bible prophecy.

In horror, my mother flicked the radio. I wasn’t moving or talking. I lay upside down on the sofa, my head dangling in midair, blood rushing to my brain, and looked up at the clock, hoping Mom would go to bed.

But my mother continued to say these were the “Last Days.” She went over to where I was lying and looked down at me. “You have to return to the Truth, Julio. I don’t want you to die in Armageddon.” From where I lay on the sofa, my mother looked upside down. Blood was running to my head and I felt hot. I could see Mom, but I really couldn’t hear her that well.

“¿Me oyes?” She punched my legs, which reached her thighs because I was still lying on the sofa upside down with my head hanging down its edge. “I don’t care what happens to that man”—meaning my father, though I knew that was not true—“I love you. El fin está cerca, Julio. So preparate, Julio,” my mom kept saying in Spanish and English.

But I was beyond that. I believed in myself, what I thought was real in me, in my inner heavens. My life was a matter of choices. I was free to make any choice. But I would be held accountable for my choices. So I always tried to choose what was right in my eyes. I no longer went to Mom’s church, the Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their elders had kicked Taína and her mother out. Yet they still believed in Mary and how she became pregnant while still a virgin. But they did not believe Taína? Why? Because it was not written in some book that isn’t even the oldest? The Gilgamesh epic is older. So are the Rigveda and the Book of the Dead. Can a book that is not the oldest book really come from the First All Powerful God? But I respected it because Mom loved it. I respected it because others loved it, too.

“Julio, el fin está cerca.” And then my mother began to cry bitterly, like she had been beaten with an iron cord. She knelt down next to me. I quickly sat upright. Blood flowed back down and away from my head, and my mother held me. And I felt embarrassed, even though no one was there, and I embraced my mother, too. And when I saw her face, really, really saw her face, I knew she had been crying before I was born. Such sadness, and maybe it was the reason she loved all those sad songs. While crying, she blamed my father for not helping enough. She blamed him for always being unemployed, and with sobs the words came out as though a dam inside had broken.

“Pa’ Lincoln”—her tears streaming—“otra vez pa’ Lincoln, if you keep believing a girl can get pregnant all by herself.”

I held my mother tight. She wiped her tears with the back of her hand. I helped her with my own palms, and I felt that she and my father had made me.

“Está bien,” she said, crying only a little bit because she had composed herself. “Sólo prometeme,” she said, looking straight into my eyes, “that you will stop trying to see that girl, promise me. Those women are trouble.” I looked into my mother’s eyes. I saw she had worked hard all her life. How she was the only one working right now, keeping us afloat.

“I will not see Taína,” I said. My mother nodded, and feeling secured, she wiped her runny nose and went to bed.

Verse 3

AT MIDNIGHT I was outside.

The roundness of the moon, like Taína’s stomach, was in full glory. It was a huge yellow moon, its glow bouncing off the project’s walls like a tennis ball. My blood was running smoothly; it was not racing with any anticipation of what el Vejigante was going to tell me. I was feeling at peace, as if this were only natural. I felt a light breeze and I leaned on the mailbox. I looked at Taína’s window across the street and waited for el Vejigante. I waited past midnight after most of the project’s windows went black; even the low glow of Taína’s window went silent.

I waited.

And waited.

The first thing I noticed was his shadow on the concrete. It was long and the lamppost’s light stretched his silhouette like a noodle. I saw him about a block away and he held not a crowbar but a cane. His cape fluttered because he walked fast, like he was in a hurry. I straightened up and was not afraid. I waited for el Vejigante to reach

me, but he crossed the street and entered our project. I knew he was going to visit the two women. My heart was happy because I was sure I was going to be asked up. Or maybe el Vejigante was going to walk out with both Taína and her mother and invite me to walk with them? I happily waited and waited and waited to see for myself if it was true that Taína, like some wonderful mysterious bird, flew only at night.

* * *

—

THERE ARE TIMES when you fall asleep and don’t even know it. You wake up and you don’t know where you are anymore. I had faded and it was really late. The sky was purple, the way it is right before the sun comes out. I was not upset at el Vejigante for leaving me hanging. I just needed to rush home before my mother woke up to go to her job at Mount Sinai’s laundry. I was about to cross the street and go home when I saw el Vejigante walk out of my project. He saw me across the street by the mailbox and smiled just a tad, crossed the street, and walked over to me.

“You’re really, really, really late,” I said, though I was still happy to see him.

“I knew you were here, papo,” he said. “I just needed to be sure.”

“Sure of what?”

“Sure that you would wait.”

“Are you going to tell Taína about me?”

“I already did,” he said. “They are waiting for you.”

I inhaled excitedly. I repeatedly thanked el Vejigante. I was ready to cross the street and enter the project. Knock at their door, this early or late, I was going to knock. I did not care about Mom or anything that minute.

“Wait, you can’t go up there, papo.”

“But you just said—”

“You see, papo, there’s always a price.”

And at that moment I realized he held aces up his sleeve. I saw in his eyes a con. El Vejigante was holding on to something. I became distrustful and a bit scared of this old man. He had been bargaining all his life, cutting corners and looking for ways in which he could get something out of people.

“Did you really do all that?” I asked him.

“Do what, papo?” He changed his stance; his body was now blocking the lamppost and it added a dark glow to his fading cape.

“What the newspapers said you did,” I said.

“When?”

“A long time ago,” I said. “You said something about not caring if you burned, and that your mother could watch. You said that when they called you the Capeman.”

“How”—he was taken aback, like this was not something he was ready to talk about—“how you know all that?”

“Googled you,” I said.

“Oh, yeah. Those things,” he said, more to himself, as if he were saying that googling didn’t exist in his world, or hadn’t in his youth.

“Did you?” I noticed he had pale and sickly skin, like someone who had spent long periods in dark places.

“No, papo,” he said in an honest tone, “no, that wasn’t me. I’m el Vejigante. Just an old man, you know, papo.”

“Oh.” But I knew it was him. He himself had told me he was the Capeman.

“You want Taína’s mother to open the door?” He was switching gears because he didn’t want to talk about the Capeman. Which was fine with me. “Then you have to visit as a friend. You see, papo, all this time you’ve been coming in as a stranger. You have to come in as a friend.”

“I am their friend,” I said.

“No, you’re a stranger, papo.”

“No, I’m their friend,” I said again, and he shook his head. The sun was coming up and he picked up his stance like he had to race home or he’d dissolve. He gripped his cane tighter; his long, thin fingers wrapped themselves around it like a snake.

“I’m going to tell you how you can come in as a friend. But if I tell you, you must agree to something, okay, papo?” He was worried of the incoming light, as if the sun could hurt him. “We have a deal?”

“Agree to what?” I said.

“I’ll tell you later. Now, do we have a deal?”

“Yes.” Because I would do anything to be a part of Taína’s life.

“So, we have a deal?”

“Yes,” I said quickly because I had to get home before my mom woke up. “We have a deal,” I said. “Tell me.”

“Okay.” And he tightened the knot on his cape and held his cane closer, as if letting me know that after he told me this he was going to run home. “Taína is looking at us right now,” he said. I looked up at her window but saw no silhouette. “She spends her days looking out the window, and guess at what, papo?”

“What?”

“At the mailbox, papo.”

“The mailbox?”

“Yes, papo. Taína is looking at the baby’s name. All day long what she is reading is the baby’s name.” And he was now ready to walk away, but first he pointed at the mailbox. “You see, Taína reads in Spanish, papo. When you knock at their door, say that Usmaíl sent you. That’s the baby’s name and they will let you in.”

El Vejigante winked at me before his stork legs took him away as daylight was breaking. I read the mailbox in Spanish. Taína spoke only Spanish, so it was as clear as the daylight that was about to break. OOS-MAH-ILL, Taína read the mailbox in Spanish, Usmaíl. When she stared out of her window, she was admiring the name of her unborn child.

Verse 4

TAKING THE 6 train downtown, I took out one of the many library books I had borrowed on pregnancy and birthing. I always thought that labor was like it was in the movies. The woman feels pain and has to have the baby right there and then, no ifs or buts. In movies women have babies in airplanes, taxis, police cars, Starbucks, but the book said it was nothing like that. Labor took time. Labor was all about time. The book said some women went to the Met during labor and stared at paintings. Some watched baseball and some took a walk through Central Park while keeping time on how apart from one another each labor pain was. It was like tracking a storm: you first hear the thunder and start counting until you see the lightning, and then you do it again; soon you know how close you are till the rains come.

When my stop arrived, I put my pregnancy book away. I then met my class by Wall Street. We were on a trip set up by two teachers. Mr. Gordon was really old, with deep wrinkles like they had been cut into his face. He moved slowly and was waiting to retire. He doubled as the guidance counselor and basketball coach. Every year I had tried out for the team. “I can’t teach height,” he’d say, and cut me. But Ms. Cahill, the science teacher, was young, good-looking, alive, and always sweet. She once took the class to visit Siena College and Cornell University, both in upstate New York, to show us how these universities are not unreachable. Told us that with hard work, a little luck, and staying out of trouble, we could attend them. Ms. Cahill had been present when Taína sang that day in chorus. It was she who said that in Taína’s voice everyone saw whom they loved and who loved them back. I wondered, who had Ms. Cahill seen? Who did she love? I knew that I loved Taína, and so I wanted to hear Taína sing. Hear the one I was in love with sing not just to me but to everyone. So that my love would not be a greedy love, like I had seen many couples display in a universe of only the two of them, but rather through Taína’s singing, it would be a love shared by all. And if Taína would not love me back, that was okay, it would suck, but it was okay because I could still continue to love her from a distance, the way Mom loves her old songs of dead singers or people who love paintings that were never alive or books or poems or ponds or places.

* * *

—

THE CLASS FIRST entered the Museum of the American Indian. They had all these Indian artifacts, arrowheads, tomahawks, and clothes made of animal skins. Ms. Cahill would lead us all over the place explaining this or that, but most kids talked over her. But Ms. Cahill was so worked up she’d say, “Think about it, there was a time in New York City when Indians stood right whe

re you are.” And someone would say, “Woopy…fucken…doo.” But she never got annoyed because someone always came to her defense: “Ms. Cahill, he’s so stupid, pay no mind.” And Ms. Cahill would laugh a little and say, “Look down at the ground, Indians sat cross-legged right here and told stories to one another. In New York City before it was New York City. You might want to write about that for your college essay.” And most would look down at their feet, though BD and I were all the way in the back.

“Usmaíl?” BD said as he kept looking at Ms. Cahill’s legs from a distance; they were long, thin, and tan. “What kinda name is that?”

“It’s the United States mail but read in Spanish.” And I said that it was el Vejigante who told me.

“Stop lying. Now I know you lying. That Vejigante don’t talk to nobody,” BD said.

“Talks to me.”

“My mom says that man only comes out at night because he’s a faggot.”

“So what?” I said. “The world is full of homos.”

“And he didn’t try anything on you?”

“No,” I said. “He’s okay.”

BD was now looking at Ms. Cahill’s ass. She wore her dresses tight, and because of the way she walked her nylons would rub against each other. If you looked closely, you could see the runs gliding down behind her legs.

“That dude comes at me,” BD said, “I’ll unhook my arm and beat him with it like he owes me money.”

“He’s a nice vejigante,” I said. “He could never hurt anyone.” Though I knew he had. “BD, I’m gonna knock at Taína’s door after school and say who sent me. You wanna come?”

Ms. Cahill and Mr. Gordon wanted everyone to go outside because we were going to walk around and use our imagination by picturing what it was like when Indians walked on Wall Street.

“Why you want me to come with you, Julio? Isn’t this what you wanted all along?”

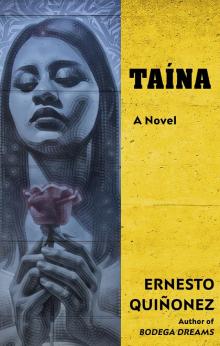

Taína

Taína