- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 8

Taína Read online

Page 8

On cue, BD’s fake arm fell off. It made a loud noise as it hit her polished wooden floors. The young lady gasped like she was out of breath, and she covered her mouth in horror. Without any inconvenience, BD picked his arm back up, relocated it, and then held his crying little brother and said, “Let’s go, fellas.”

“Wait!” the lady cried out, as if she had done us a disservice. “There is a reward.”

* * *

—

OUTSIDE. ON PARK Avenue we turned the corner and started running. We would have continued maybe all the way back to Spanish Harlem, all the way back to 100th Street and First Avenue, except that Ralphy was too little and he got tired.

“You said you were going to buy me a hundred penny candies if I cried.” Ralphy was upset at his big brother.

“I am,” BD said, and gave him a Jolly Rancher. We were in the street, and I wasn’t going to take out money. So we went inside a pizzeria, ordered pizza and Cokes, and sat all the way in the back. I began to count. It was a lot of money, and I could almost see Doña Flores’s happy, smiling face.

Verse 3

EARLIER, I HAD arrived with two bags of groceries, Pampers, talc, wipes, blankets, Cokes, a manicure set, Q-tips, chewing gum, Blow Pops, Lemonheads, Nerds, Kit Kats, and a lot of junk food because I had read in the books I had borrowed from the library that pregnant women ate a lot of junk food. I knocked and waited. I then realized that Doña Flores was not going to open unless I slipped the envelope with money under her door. So I did. I soon heard the sound of bills being counted, the whispering of numbers in Spanish. Only then did the locks clack, and she opened the door only wide enough for me to enter sideways with the bag of groceries.

Doña Flores’s face was pleased. She spoke to the wall in a very surprised Spanish, “Juan Bobo did it.” I corrected her that my name was Julio. She nodded, but I knew she was laughing at me. Laughing at me with the walls she talked to. But I didn’t really care. I could hear my heartbeat doing those circles around circles and retracing those same circles because I was soon going to see Taína.

I had told Doña Flores that I was in love with her daughter, and though I was sure, I didn’t know how to tell Taína this. I was also afraid of her potty mouth.

I walked inside and Doña Flores stacked the cartons of diapers on one side of the empty hallway. In the living room, Doña Flores motioned for me to wait. With one hand she held the money, and some of the groceries with the other. She knocked at Taína’s door and said, “Ta-te.” And the circles in my heart were now forming other shapes and figures, floating, wiggling, and bouncing inside me like some abstract painting and all I could do was look at the floor.

“¿Tú eres Julio?” Taína said in a Spanish that sounded delicate. “That’s a pretty dumb, stupid fucking name.” She switched to English: “The dumbest, ugliest shit name I have ever heard.” But it made me happy she thought my name was pretty dumb and stupid. “You shouldn’t look at people when they are in the fucking bathroom,” she scolded me with the tone of a command.

“Yeah, yeah, I’m sorry. I was just there,” I answered, looking at the floor. I would have smiled at Taína, but I wasn’t able to look up. I was scared to be blinded in some nervous way. I simply looked at Taína’s chancletas. They were a plastic orange. All her ten toes showed chipped remnants of cherry-red nail polish, and there was a big Snoopy Band-Aid taped across her big toe. When I did look up, a thin cotton blue-gray see-through gown the color of a seagull’s eye covered her pregnant body. The gown was wrinkled, as if she had slept in it. It was hard not to pay attention to those places that boys are not supposed to stare at. And so I kept my head down.

“Do you like pizza?” I said, looking not at her but rather at Doña Flores, who was putting away the groceries. “You know pizza?”

“Pizza?”

“Pizza, to eat?” I said, and tried not to smile too much. To not look at her see-through gown, though she must have known that her brown nipples were poking out as if they, too, were making fun of me. “Pizza, it has cheese and stuff.”

“I know what pizza is, you dumb fuck,” Taína said. “Of course I like pizza, you dummy, you stupid idiot. Pizza tastes good. Who doesn’t like pizza?” she said in perfect English. I was taken aback. She could speak both, probably read in both, too. Taína then laughed like this was the most fun she had ever had.

Doña Flores went to the kitchen, and we were left all alone in the living room. I finally looked up at Taína’s face, but my eyes were caught by her breasts. My clothes started to feel really tight, and my eyes would not go above her chin. They simply continued to be stuck there. Taína exhaled like she was bored. Her breasts rose up and then came back down. Her entire gown waved in the air. “Boys, please…” She exhaled again and went to her room. She came back wearing a T-shirt over her gown that read: PROPERTY OF THE NEW YORK YANKEES.

“Are you eating well?” I embarrassingly asked in English, as I now knew that Sal had not told me the truth.

“I like Twinkies. You better have brought some. You brought ice cream? Right? Right? And gum, too, stupid? I’ll kill you if didn’t.”

“Yes, yes, yes, I brought gum,” I said, but was mad at myself for not bringing Twinkies. I didn’t tell her that Twinkies were bad for you.

“I miss reading magazines,” she said, like she was bored. “I like to read. The books in this house are all religious shit, Watchtower and Awake! shit, really stupid shit.”

“Do you want me to get you books?”

“Didn’t I just say that? God, you can be so dumb.”

“What do you like?”

“Anything, but especially magazines. I like books, but I like magazines more.” I remembered the night I followed all three of them as they entered a store.

I wanted to ask her if I should buy her a boom box or an iPod so she could listen to music. I knew she sang. But I didn’t know how to get to this point.

“Do you miss school, Taína?” She took a little longer to answer because I think she didn’t want her mother to hear us. All she did was shake her head slightly.

“Sometimes. Yeah, I miss school.” She shrugged. “I don’t miss some of those stupid kids making fun of me.”

“Do you miss singing?”

“How’d you know?”

“Ms. Cahill told me—”

“Oh, her? She was nice. Yeah, I sang, no biggie. Just stupid shit.”

“Do you want me to get you an iPod?”

“Those things? Why?”

“So you can listen to music,” I said, as if it were obvious.

She shrugged like she didn’t care, but I knew she did. I didn’t know if I should ask her, it was a stupid thing to ask, but I did.

“Can you sing? I mean, just a little. Nothing big.”

Taína’s mouth quickly opened in disbelief. As if I had asked her for something obscene. As if I had asked her to flash me. She then closed her lips, crossed her arms, and smirked.

“Do you see a hat anywhere?”

“A hat?”

“Yeah, so you can throw in a dollar—I’m not fucking singing for you, bitch.”

Doña Flores was done putting away the groceries. She then sat at the kitchen table budgeting the money and making notes on a pad.

I let the singing go and looked straight at Taína’s face. I noticed constellations forming around her eyes and nose and I stupidly said out loud, “Taína, you have freckles.”

“Fuck you,” she snapped. “Yes, I have fucking freckles, and Usmaíl will have freckles, too. You got a problem with freckles?”

“No. I, I like freckles. They’re cool.”

And then though her belly was big, she had no trouble sitting down on the couch. I sat at the very far end of the couch to give her pregnant body room. Taína scooted over to be closer.

“I hate my name,” she

said. “Usmaíl is the only name that’s not stupid. I like looking out the window at the mailbox. I like to read it in English.”

“It’s a magical name,” I agreed.

“Not like my name. I hate my name. My name is stupid,” she said.

“I like your name. It’s very pretty.” I wanted to kiss her, but I didn’t know how to kiss. I don’t think she knew how to kiss either, no matter how much she cursed. But I would never dare. “You know I believe you, Taína.” I looked straight at her, tried hard to keep my gaze at her eyes. “I know what has happened to you. I know.” I was anxious in telling her. “Something happened inside your body where you got pregnant all by yourself.”

“Okay, tell me.” She crossed her arms like she was bored.

“Do you know what a cell is?”

“Yes, of course I know what a fucking cell is.”

“Okay. Do you know what an atom is?”

“Yes, yes,” she said, like she was bored, “everything is made out of them. What is your stupid point?”

“Okay, okay.” And I told her about the revolution that had occurred in her body and how she was special and had been chosen by this revolution. How this revolution could not have happened inside any other body. I told her about an atom that refused to follow the law of her DNA. And it rallied other atoms in sharing electrons and expelling them, too, in order to form the molecules needed.

“That is the biggest…load…of bullshit…I have ever heard.”

“Fine.” I felt her laughing eyes. “Fine. Fine. Then how’d you get pregnant?”

“I don’t fucking know, Julio. If I knew, I would tell everybody. I feel really, really stupid, that as a girl I don’t know how this happened. But I don’t know…I don’t fucking know.”

“You not lying, right?”

“No, I’m not. I really don’t know. If I knew I would have told Mami. But I swear I don’t know.”

I was disappointed she didn’t believe me, but I was happy when she scooted her body even closer. For the first time her voice was warm, as if telling me that this was no lie. “I don’t remember anything,” she said, shaking her head. “I only remember feeling shitty one day and then my mother went to the store and got a stupid fucking test. I peed on it and it said I was freaking pregnant. Worst is I don’t remember anything, anything of how it happened, Julio.”

“Nothing?” I looked at her bare legs full of gooseberry fuzz and shine.

“I do remember your gifts by the door. We emptied them and threw the boxes away.” So my gifts had been accepted after all. What I’d seen on top of the garbage heaps were the hollow boxes.

“But what about the bassinet?” I said, leaving her legs and looking straight at her. “I got you a bassinet and you never took it.”

“A bassinet? Come on, shithead”—and she sucked her teeth—“who really needs a bassinet? A crib, yeah, but a bassinet, come on. A bassinet? Who the fuck you think we are, the royal fucking family?” She must have noticed my disappointment or something because her tone became softer.

“I remember you from school. You were nice. You never said mean things to me. I would see you and not be afraid. I would see you from my window standing by the mailbox and feel bad for you.” When she saw that my face changed, she changed. “You happy now, God?”

“Fine,” I said, as this was whom I had fallen in love with and I did not care. “But you don’t feel a revolution inside you? Not even a little bit?”

“Nope. I think that what you told me is pretty stupid. Mami says that only Peta Ponce can get to the truth of what happened.”

“The espiritista?”

“Yes,” Taína said. “And you are paying to bring her.”

And I don’t know when Taína’s hand found my hand and guided it over her warm stomach.

“Usmaíl,” she said. And I felt two poles holding up a circus tent. I wanted to giggle, not laugh but giggle, because it was like Usmaíl was inviting me to play. Then the poles went back inside her, but Taína let me keep my hand on her stomach. Taína fixed herself even closer to me and laid her head on my shoulder. She wasn’t smiling or anything, but at least she wasn’t cursing. I think she was a little tired. Her hair was spilling on my shoulder and I looked at a single strand.

And I saw things.

I saw Taína’s DNA.

Its strands wrapped together like hands holding each other, its fingers entwined like ropes. I could see all the subatomic particles, its circuits of atoms like thrilling stars shimmering, pulsating in Taína’s inner heavens. I could see deep into the revolution that had given birth to Usmaíl. I saw all this empty, empty space that was not filled up by any form of matter. And then I saw a baby. A baby jumping from atom to atom. There was electricity all around the baby exploding with laughter. And then the baby saw that I was there. I was laughing, too. The baby opened its hands and showed me colors. New colors concealed deep inside stars, new colors existing in hidden dimensions where the chemistry of light is poles apart from the chemistry of our world. Usmaíl showed me prime colors no human had ever seen. All these unseen reds, all the unseen yellows, all the unseen blues, the mystifying colors concealed within the wastes of subatomic supernovas. And then I was back in Spanish Harlem.

Back in the projects.

Back on the couch.

Back to where Taína had fallen asleep on my shoulder. Her pink lips sweetly parted and her breath hinted of orange Cheetos. I was happy that I would take with me the scent of her breath on my shirt. The way her voice seeped into your clothes and you could never wash it out. Taína breathed peacefully. I gently brushed her hair, knowing I would always be in love no matter what insult she dished out. I wanted to be next to Taína, to smell the peach shampoo in her hair, at least that was what it smelled like, to see the tiny hairs inside her ears, to count the freckles on her face. I did not care that Taína did not believe me. I knew a revolution had occurred in her body. I thought about this espiritista and thought maybe this Peta Ponce would finally validate the revolution.

Doña Flores entered the living room and found us sitting close to each other but didn’t say anything. She just gently tapped my leg. I needed to go. “Gracias, mijo,” she whispered so as not to wake her daughter. “Mira, Juan Bobo, Ta-te needs her rest.”

Verse 4

I WALKED IN with a new dog. My mother was on the phone and the radio was on low volume. I didn’t know the singer, though I think it was Juan Luis Guerra, a bachata. There was a bag of groceries standing on the couch by the living room. Mom was happy to see the dog because the last time I had given her fifty dollars. My father was very proud of me, too, telling all his pinko friends from Ecuador that I was a man who contributed to the house funds. I wanted to openly contribute more money, but I could not explain all this income I was scamming. So instead, I’d sneak a hundred here and there inside my mom’s boot in the closet and she’d never know the difference.

I sat at the table and ate what my father had cooked. Mom kept talking to whoever it was she was on the phone with.

The past day with Taína was all I had been thinking about. I felt like I had been given a gift at seeing some celestial creature that had to be kept secret.

After eating, I fed the new dog that BD and I had borrowed and then gave it water.

I was about to go to Salvador’s house when my mother stopped talking on the phone for a second and asked me where was I going.

“To hang with BD.”

“You sure?” she said, and excused herself to the person on the other line and got back to me. “Because I got word you were on the second floor knocking at that crazy woman’s door.”

“Ma, I go to school,” I said, insulted, “and now I have a job. I don’t have time to do anything.”

“Mira, Julio, Inelda was seen out on the street buying stuff.”

“So?” I shrugged.

/>

“That woman hasn’t shown her face and now all of a sudden…?”

“And now what?”

“You still hearing voices?”

“I never heard voices, Ma.” But her eyes continued to check my face for things that only mothers can detect.

Then just like that, her face changed and she let it drop.

“Dios te cuide,” she said. “Don’t be home late.”

I was about to leave, but this time my father came over from the bedroom.

“Can I walk the dog?” he asked me in Spanish.

What if my dad took the dog for a walk close to the Upper East Side? What if someone recognized the dog? What if then they went to the cops?

“Sure, yeah, okay, Pops, but don’t go very far.” I chanced it because it made my father so happy to feel like he was working.

“Thank you. Now, I am not taking away your job,” my father said in Spanish. “No one is saying I want to take your job. I just want something to do. That is all.” My father went on to put on his best shoes and good clothes because the neighbors would finally see him doing something. My father was even whistling some Ecuadorian song. And this made me happy because I felt like I had hired my dad.

* * *

—

SALVADOR OPENED THE door, covering his eyes from the glaring sun. He was holding a grilled cob of corn with mayonnaise spread all over it and drenched with Tabasco sauce.

“Mejicanos eat it like this,” he said. “It’s not bad. You should try it, papo. Me? I’m happy I still have teeth and can eat this, you know, papo?”

There were a lot of Mexicans living in Spanish Harlem. Their tastes and food carts were all over the neighborhood. They flew their flag like we flew ours. But now the eagle of their green, white, and red was overtaking the neighborhood. The Mexican flag fluttered all over El Barrio, and it seemed that we liked them and they liked us because there wasn’t as much pushing around, as had been the case when we arrived and the Italians wanted to kill us.

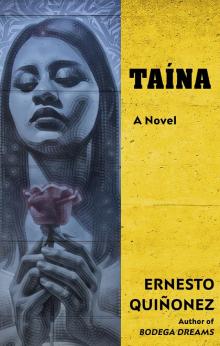

Taína

Taína