- Home

- Ernesto Quiñonez

Taína Page 9

Taína Read online

Page 9

“You should try their grilled mangoes,” Sal said, letting me in. “That’s good stuff. They put pique on everything. Man, if I had money I’d eat this every day. It’s good, this is a treat for me, you know, papo? I’m lucky I don’t have high blood pressure, just type two. But who cares, papo.”

I walked past all the old television sets stacked against the short hallway.

“What are you doing with all these sets, Sal?”

“Gonna fix them, sell them,” he said, as if it were obvious.

He must have found them on the sidewalks as he strolled at night. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that nobody really bought these old square sets anymore.

“Are you going to fix that piano? Sell it, too,” I said, pointing to the biggest thing in the living room.

“No, no,” he said. “That was a gift. Hey, you wanna hear something? I can play something for you, papo. Really.”

“No, it’s okay. Here,” I said, taking out a wad of twenties.

“You sure?” He could not believe it. “How much you got?”

I told him.

“Okay. That’s not so bad.” Meaning when he ran this scheme he must have done better. “You need to go after pure breeds. I once borrowed a baby Labrador and man, I struck it rich.” He finished his corn and started sucking on the cob. “So, you saw Taína?”

“Yes, she’s beautiful, but why does she have to be so nasty sometimes?”

“Really? I never noticed.” He picked his teeth a bit.

“She curses all the time, and everything is stupid this, fuck that.”

“Never noticed.” He licked some mayonnaise off his fingers.

“And you said she can’t speak English.”

“No, papo. I said that she reads the mailbox in Spanish.”

“Never mind.” I let it go because it was hopeless.

“You want to keep seeing Taína?”

“Of course.”

“Then get the money so Peta Ponce can come over here, papo,” he said, as if there were nothing wrong with this exchange. He opened his refrigerator. “You want something to eat? I got beans. I got cheese. I got bread, and this time they gave us bacon. Don’t know where Uncle Sam got the pigs, but it’s good bacon, too, papo.” He saw my look of discomfort. “Listen, papo,” Salvador said, closing his refrigerator. “I don’t blame my sister for what she is doing. You know she grew up during a lot of violence in New York City, you know what I mean, papo?”

“So what? My mother did, too. And she’s fine.”

“That’s right, because your mother still has the church. In the church she found her salvation, papo. Inelda did, too. But what happens when the church kicks you out, huh? What happens when your line of survival is cut? When Inelda joined the church, she was already a wreck, having grown up with violence, and when she was cut by her church she became desperate. She could pray to God all she wants, but nothing is going to happen. I knew this. I knew this, so I said to her, ‘God will send someone to help you.’ ”

“Who’s that?” I said.

“You!” He pointed at my chest. “You, papo. God sent you.”

“God did not send me.” It was the most ridiculous thing I had ever heard.

“I told her He did. You all she has,” he said. I knew Doña Flores thought Salvador was a saint, so she’d believe anything her brother told her.

“She can always come back to the church,” I said. “They can help her.”

“No, she cannot,” he said. I saw the vejigante costume hanging by the closet was a bit wrinkled and wondered if he had worn it someplace. The ¡Puerto Rico Libre! button was a bit crooked, too. “Inelda is too far gone. When this happened to Taína and they were kicked out of the church, she lost it completely. She’s too far gone, papo. Don’t you understand that?” And he circled a finger around his ear and whistled. “She’s gone. She’s cuckoo. You must have seen her talk to walls? And I can’t help her because I’m an old man and I’m gone, too, you know, in my own way I’m gone, too, papo. Prison—” And he caught himself fast because he had never said the word before. It had slipped out and he tried to lasso the word back into his mouth, but it had already been set free. “It does things to you. You know, for years living with people who are broken beyond repair but continue to live, it does things to you. So when you do leave there, you take that place with you….I’m gone in my own way. Listen, papo, poverty is violence. They keep us poor so we can lose it and then they can blame us.”

“I don’t know. The Man this, the Man that? Come on, Sal,” I said, because this all sounded like some excuse.

“Good,” he said, noticing me looking at his costume, but he was not going to put it on. “Good. Because if you believe that, papo, you stop. You stop right now. You don’t borrow any more dogs, and just go home to your mother and her God and never see Taína again. You don’t help her or anyone, because if you do, you lose time in running on the poverty treadmill they have placed us on. They are evil people. Poverty is violence, papo. And it’s worse on women and children.”

For the first time I saw anger in el Vejigante’s eyes. Anger toward many things, including me. But he would not let that anger be set free, as if he had learned what it had made him do that night long ago.

“Listen, papo, they want to keep us poor.”

“Who is ‘they,’ Sal? The Man? Who is the Man? Who is keeping us poor?”

“The capitalist system, the wealthy, the politicians, the police, everyone who benefits from you dying paying rent, papo. That’s the Man,” he said, sounding like someone from another time, another moment, in American history. I knew that I loved Taína, but Sal was becoming this bore. “Violence doesn’t always come with a gun, papo. It can come with policies that are put in order to keep people like us in their place.”

“I got to go.” I had come for answers and he had given me politics. I was thinking of not visiting him again. I was going to deal with Doña Flores on my own. Somehow one day soon, I was going to stop borrowing dogs. Help Taína and the baby some other way.

“Later, Sal.”

“Hey, papo…” He stopped me. “I’m gonna tell you this because it belongs to you, okay? It’s yours by law. Because, papo, when you love someone you burn the sky if you have to in order to feed them.”

“I gotta go, Sal.”

“Promise me two minutes, okay? I’m an old man, two minutes to me is a lot. But for you, it’s a cigarette, okay, papo? Just two minutes.”

“Fine.” I exhaled out of boredom.

“Okay, listen, I was in there for many, many years, but while I was in that place”—and he licked his lips and took a breath—“Inelda was young and she was her family’s only source of income. You know how fathers are, never around or never working, so she was it. She liked to sing. She was really good at it, too. You would never know it from looking at her today. But Inelda was great. For years she would kick money my way and my commissary was okay, at least better than most. You know, papo.” He saw me move toward the door, so he quickened his speech. “She was very popular, had a lot of boyfriends. Then she met this Puerto Rican guy who hated other Latinos. She never married him, but she did live with him. But when Inelda became pregnant, he took off. It was your mother who knew about this doctor who could make sure Inelda never got pregnant again. Inelda didn’t want to do this, but the doctor said it was best and she had to feed her mom and soon the baby, too, and after this she could date all the men she wanted with no problems, that doctor said. Your mother agreed with that doctor. You know what I mean, papo?” I started to understand why Doña Flores talked to walls. “That was the beginning of my sister’s mental problems. All she’d do was cry all day and all night, you know, papo, never sang again. Your mother, Julio, was her best friend. And it was your mother who had heard about this woman who was famous around Puerto Rico and here, too. They

say she could heal broken women. Your mother took Inelda to see Peta Ponce.”

My mother didn’t want me to see Taína. Now I knew why. I felt very sad, like the bottom of my life just fell.

“And Peta Ponce helped Inelda, but she was never the same. Your mother, papo, knew about these things because she had been in Inelda’s shoes.” He cleared his throat and checked my face. “After you were born, ella lo hizo. You know, she needed to work to keep you alive, so ella lo hizo. It was that or welfare. So when the same thing happened to her friend, your mother did what she only knew, la operación, you know. Ella se lo hizo, it was so ingrained in the culture that it seemed like nothing. But of course that is not true, otherwise these women wouldn’t keep it a secret, and Peta Ponce helped your mother deal with that shit, too.”

I had never asked why I had no siblings, but now I knew.

“Papo, don’t cry. Listen, I got cornflakes, papo. I got a banana that’s still good. I got these cans of milk, okay, papo? Don’t cry.” But I kept crying. “I can make you a cereal bowl with bananas and powder milk.” I kept crying. “Oh, and they gave us soda, don’t cry. Listen, you want some soda? Don’t know where Uncle Sam found the soda but they gave us soda. You want some soda, papo? Don’t cry. This viejo likes your company, don’t cry, man.”

Verse 5

AS SOON AS Mom walked in tired from work, I had a bucket of hot water with Epsom salts and the radio turned on. She laughed and called it a miracle. The miracle, I thought, was that she actually let me wash her feet. I sat her on the sofa and removed her shoes. Soledad Bravo sadly, sweetly, and beautifully sang a cover version of “El Violín de Becho.”

“Who died?” was all she kept saying as I scrubbed her calves and let her feet soak in hot water. I simply laughed because I had never done this but was happy to be doing it. I had a towel to dry them, too.

“Feeling better, Ma?”

“You want something, right, Julio?” she said.

“No.”

Soledad Bravo sang beautifully about a violin that is left alone on a corner.

In the kitchen my father was cooking up a magical storm. Whirlwinds were swallowing up chickens and meats as Ecuadorian spices sprinkled from his fingertips like static electric bolts. He’d throw meats into saucepans that sizzled like an audience clapping and smoke would rise and drift all around the apartment like a blue-gray genie. Our white whale of a refrigerator would open and shut as he mugged it, and then he walked into the living room, angry hands on hips.

“Out of vegetables!” he complained in Spanish. “How can we be out of vegetables?”

The reward flyer had said that the dog was a vegetarian, so I had fed that little yellow dog all the vegetables. I had already taken the vegetarian dog back and collected the hefty reward, but I had forgotten to replace the vegetables.

“I’ll go and get some, Pops,” I said.

“After you are done,” my mother said before going back to humming.

And then, as I continued to wash my mother’s feet and as she sang along to such a sad tango, I had a vision.

I saw Mom.

I saw her as a seven-year-old.

A little girl swimming in the Caribbean Sea. She was paddling and smiling and never feeling lonely. The salt water reached her lips as she tasted the Puerto Rican sun. The sky sheltered her from above, and I knew that a child who bathed in those waters could never feel poor. Then I saw her on a plane, then arriving in Spanish Harlem. I saw how she was made fun of by the older kids who had arrived here first. And I saw a little girl in school feeling lost among a sea of children who spoke a language she had yet to understand. I heard her learning those early songs: “pollito, chicken / gallina, hen / lápiz, pencil / pluma, pen.” In Spanish Harlem my mother felt poor, and the city made sure she felt lonely. I saw her as a sad tropical kid growing up in a freezing tenement. A kid walking home alone after school. The apartment key dangling by a string tied to her lovely neck. Walking among piles and piles of uncollected garbage at her sides. The streets of Spanish Harlem of her time always dirty and broken. A kid coming home to a dark house. How she’d whistle to keep herself company as she did her homework and reheated last night’s dinner, waiting for her parents to arrive from their factories. That little girl that would become my mother lived there until the tenement soon met its end by arson, and later she lived in a welfare hotel until the city placed her and her parents in the projects.

And then I saw my mother older but young still.

She was pregnant.

I was still cooking inside her.

I saw her panic. I felt her fear of more children and my father’s chronic unemployment. And then I saw her on the hospital table.

And then I was back in our living room.

Back washing my mother’s feet.

Back to Soledad Bravo singing.

Ya no puede tocar en la orquesta / Porque amar y cantar eso cuesta.

All that mattered was that Mom was happy. She splashed some water on me while I was getting the towel ready. At that second I felt like a little kid.

My father was grumpy.

“Hurry up.” My father huffed. “My food cannot wait.” And then he began washing the dishes, caressing them like wet babies in his hands and laying them gently on the drying rack.

I dried my mother’s feet and kissed the left one. She pulled it back.

“Gross,” she said, but laughed.

“Ma,” I said, as I was about to get my father’s stuff, “it’s going to be all right. Don’t worry, it’s all going to be all right, okay? It’s all going to be fine.”

Verse 6

IT’S HARD TO see my mother young and great looking, but she was. Family stories have it that when Mom turned eighteen she convinced her best friend, Inelda Flores, to dye their hair. Mom would be the Blonde and Inelda the Red. She hoped that they’d be known throughout Spanish Harlem as la Rubia y la Roja, but everyone simply called them las Chicas.

The Girls danced like they were born inside a conga. Mom and Inelda hit all the dance clubs of their day, Corso, the Latin Palace, Palladium, the Tunnel, Boca Chica, Limelight, Cafe con Leche, Tropicana, the Latin Quarter, whether salsa, charanga, mambo, merengue, boogaloo, cumbia, guaracha, plena, bomba, disco, bachata, house, rap, reggae, whatever was playing you could find the Girls, dressed to the tens. They’d eat, drink, and dance. Did they smoke? Of course. Every Saturday on a hot summer night they’d break their religion’s rules about not just smoking but socializing with people from the “world.” Did they kiss boys? Of course, but that’s as far as they went, because what they really lived for was their weekend away from their jobs and families. Mom was a perfume salesgirl, standing all day, spraying people at Gimbels on 86th and Lexington, while Inelda xeroxed other people’s documents at Copy Cat across town on the Upper West Side. Both had just graduated from Julia Richman High School on 67th and Second and were enjoying their newfound freedom and small paychecks. I heard my grandparents hated that Mom and Inelda acted this way. “This is what machos do, not ladies,” they’d say to them. The Girls lived two lives, one as saints for the elders at their Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses and the other as the Girls on an endless quest for the perfect night, the perfect dance number, the perfect drink, the perfect kiss, while breaking hearts that fell and splintered like dropped porcelain. They lived for a sea of scratched records on dance floors built on springs. The Girls liked double-dating boys from the neighborhood who they knew liked to play big shot and spend all their money on them. These clubs were cheap to enter, the price was the long line one had to wait in, but inside it was the drinks that would rob you, hence the big shot boys.

Everything was different then. Many of the Fania All-Stars were old but still kicking and playing. The Girls caught a set at the Palladium with the Joe Cuba Sextet, a nontraditional Latin dance band of old-school architects who had merged

black America’s R&B styles with Afro-Cuban instruments. The Girls loved how Joe Cuba infused elegance by adding cool violins and smooth flutes to his band’s sound in order to balance the macho horn section. The Girls loved Joe Cuba because his boogaloo was so conducive to spinning, and what girl does not like to be spun?

On payday, they’d hit Casa Latina on 116th Street and spend a good chunk of what was left of their hard-earned money on records and cassettes; they’d hit Casa Amadeo in the Bronx, too. Later, the Girls would grab a ghetto blaster and walk to the north side of Central Park to sunbathe. They’d turn the dial in search of old dance tunes, Machito’s “Live from the Copacabana, 1959” or “Celia Cruz en El Club Flamingo Havana, 1965,” broadcast on WHNR or WMEG. They’d bring their own drinks and ice and let the sun bake them like gandules. Back then, kids fished the Harlem Meer, teens on Rollerblades skated by, and families barbecued. A different city, crime was high, and they lived with it. The Girls knew to stay together and that all it took was common sense, a little luck, and safety would take care of itself. Just stay together was their mantra, never to be broken. Stay together. They knew the places to go in Central Park and which places not to. It was the same on Saturday nights: they knew to always have cab money—don’t take the subway after nine p.m. But the dance clubs, that was where the gloves came off. The Girls would do as the music dictated but always staying together.

I’ve seen pictures of my mother back then, thin, push-up bra, fake blond hair, fake green eyes, legs for days, and a waist so thin it looked like she could be cut in half. Mom looked too beautiful to be real because, simply, she wasn’t. Her Taíno cheekbones, olive skin, red puffy lips, and Indian features contrasted so heavily with the long, lush, dyed blond hair and green contacts that no matter how striking, how gorgeous, you knew it had to be fake. God or nature could never dish out that much color to any single person. But the men never cared. Family legend has it that one night at the Park Palace on 110th Street and Fifth, as the Girls were fanning their sweaty faces after a Wilfrido Vargas merengue—Mami, el negro está rabioso / Quiere bailar conmigo—a man dressed like it was still 1970 with the widest shirt collar and elephant bell-bottoms asked my mother if she wanted to be on the cover of his next LP. The Girls recognized Héctor Lavoe immediately. In front of them was one of the people who had invented their reason to live. Speechless and hot and flattered, they did what most girls do when together: they went to the restroom and had a conference. Like everyone who loved the Fania All-Stars, the Girls knew that Lavoe was not really a skirt chaser. All he cared about was his music and what he shot up his arm. So they figured it was safe and Inelda would tag along just in case, remembering their mantra, “Stay together.” This would be their secret. If the church elders ever found out, my mother would deny it, she’d tell her elders that it wasn’t her, looked like her, but it wasn’t her and Inelda would back her. They had a plan.

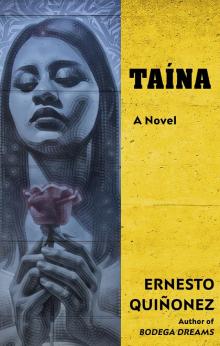

Taína

Taína